Here is Clayton Chrusch’s detailed summary of Chapter Five of Fearful Symmetry:

The greater the work of art, the more completely it reveals the gigantic myth which is the vision of this world as God sees it, the outlines of that vision being creation, fall, redemption and apocalypse.

1. The Bible as archetype of Western culture

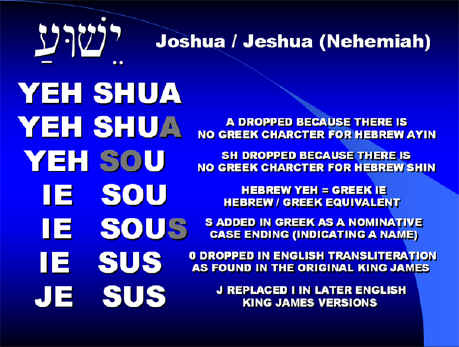

For a Christian, the totality of creative power is called the Word of God or Jesus. This creative power sees a vision of all time and space whose mythic shape is the same as that of the Bible: “creation, fall, redemption and apocalypse.” Frye writes, “all works of art are phases of that archetypal vision,” and the greatest art, such as the Bible, most completely reveals this vision.

Blake viewed the central myth of the Bible as a genuine vision of reality, and his work as aligned with it. This Biblical vision is an imaginative one, however, and Blake dismissed as irrelevant questions of historical veracity. Blake also rejected what he considered stupidly orthodox readings of the Bible of the kind that attempted moral justification of God’s Old Testament bloodthirstiness. Rather he saw such passages as true visions of a false god, and he saw such perverse orthodoxy as Anti-Christ. The Bible, though, is not a unique or exhaustive expression of the Word of God, rather all nations, in Blake’s view, had the same genuineness of vision, though the ancient Greeks in particular obscured and forgot theirs.

In art, the most complete vision is cyclic, and in poetry this complete form is called epic and properly covers “the entire imaginative field from creation to the Last Judgement” though, like the Bible, it is most concerned with the the world’s cyclical movement between the opposite states of falleness and redemption. Non-epic forms can be considered as particular episodes within the universal epic vision. As such, literature, at least Western literature, can be seen as more conventional than is commonly acknowledged.

2. The poet’s meaning is often different from what he thought he meant.

Blake sees creative actions as an artist’s real life. Actions and thoughts “on the ordinary Generation plane” may have nothing to do with an artist’s creativity. This is why Wordsworth’s preface to the Lyrical Ballads is “twaddle,” while the poems themselves are clear visions, and why in general we cannot trust or limit the meaning of art to the artist’s conscious intention. The real intentions that produce art are often sub- or super-conscious.

3. “Reality is intelligibility, and a poet who has put things into words has lifted ‘things’ from the barren chaos of nature into the created order of thought.”

Blake held diction to be very important though he makes few statements about it. His position begins, as it usually does, with a rejection of Locke, in particular, he rejected the notion that words are inadequate substitutes for real things. On the contrary, words make things intelligible and therefore more real. The meaning of a word, beyond generalities, is undefinable because it depends both on its context and its relation to human minds. The sounds, rhythms, and associations of a word–attributes that have little to do with its general definition–are functional in poetry and can give a word a meaning that is beyond the capacity of any dictionary to capture.

As for rhyme and meter, Blake insists that “the sound, sense and subject are to make a complete correspondence at all times” which means that fixed stanzaic patterns may be appropriate for short lyrics but rhyme is dropped in the longer works and meter and line length are varied according to the content.

4. Right and wrong kinds of allegory

We should understand poetry by unified and immediate perception. We might have to do hard intellectual work in order to unify the poem in our minds, but it is the direct experience that is the meaning of the poem. The intellectual scaffolding that helped us achieve that experience should just fall away. “For,” as Blake writes, “[a poem’s] Reality is its imaginative Form.” The wrong kind of allegory is “merely a set of moral doctrines or historical facts, ornamented to make them easier for simple minds.” The wrong way to read allegorical literature is to reduce it to such a set of abstractions. Great allegorical writing exists, and it is great not because of the quality of ideas it represents but because of the imaginative power of its vision.

5. The power of religion lies in its poetry.

We cannot hold to art as good or true because art envisions both good and bad, true and false. Religion does claim sure and reliable knowledge of truth and goodness, but there is something false about this claim. The power of religion lies not in dogma but in the visionary masterpieces that the dogma is derived from. The poet’s task is to go back to the symbols of those masterpieces and to recreate them. The meaning of these symbols (for example, the gods of ancient Greece) becomes more vague over time and the artist’s function is to clarify it.

This is what Blake does. One of his tactics is to use unfamiliar names for his characters. Though he could have called his sky father Zeus, Blake called him Urizen to head off the vagueness that comes with Zeus’s large cloud of associations.

Christianity is not more true than other religions, but its imaginative core, what Frye calls, “its vision of the humanity of God and the divinity of risen Man” is that characteristic imaginative accomplishment of Christianity that “all Christian artists have attempted to recreate.” Even secular writers like Shakespeare and Chaucer are informed by “the universal Word of God, the archetypal vision of ‘All that Exists.'” This vision provides the most profound kind of signficance to all worthwhile art and makes such art allegorical in the sense Dante used when he spoke of anagogy.

6. In art, all creatures are human.

Frye writes, “It is the function of art to illuminate the human form of nature.” By this he means that art “interprets nature in human terms.” Only a human being can create a design, but that does not stop art from seeing design in the pattern of a snowflake. Blake’s tiger has a human creator that makes the tiger’s form, which is therefore a human form.