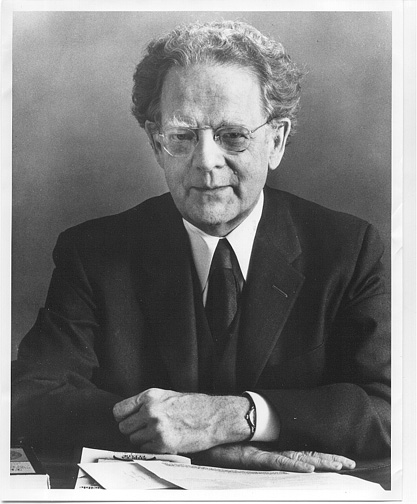

One of the delights we have every April is introducing Frye to authors who have never heard of him and are curious to know more, as happened, for example, when Bernhard Schlink was here in 2004. Sometimes we are surprised when an author reveals a personal connection to Frye that we didn’t know about. Last year Don McKay, one of Canada’s great poets, took delight in telling the story of his mother’s encounter with Frye in the 1930s, when she took a class from him that influenced her at the time and later, toward the end of her own life, came back to inspire her when she wrote her memoirs. Andy Wainwright, Ross Leckie, and others studied with Frye and have fond memories. Peter Sanger has a longstanding interest in Frye; and, unless I’m mistaken, also studied with him. Richard Ford was familiar with Frye from his student days in the 60s. (Ford’s complete conversation with Globe and Mail’s Books Editor Martin Levin can be seen via the festival website’s U-Tube link.)

Robert Bly, who was here in 2001, said, in accepting our invitation, “Frye is one of my favorite people.” There’s a lot of common ground between the two that would be worth exploring, even if the direct influence each way is perhaps minimal. Blake’s “the tigers of wrath are wiser than the horses of instruction” is where they both begin, in their thinking about education. The idea of freedom is at the centre of everything they do. Neither shies from talking about and mapping the spiritual world, even when such activity is out of fashion. But what especially interests me is Bly’s idea of ‘deep image’ in comparison with Frye’s analysis of existential or ecstatic metaphor. Though ‘deep image’ suggests a location in the psyche, Bly prefers to think of the image as a place “where psychic energy is free to move around” (as quoted in Kevin Bushell’s essay “Leaping Into the Unknown: the Poetics of Robert Bly’s Deep Image”). Frye says, “Metaphor is the attempt to open up a channel or current of energy between subject and object” (as quoted in Bob Denham’s Northrop Frye: Religious Visionary and Architect of the Spiritual World, p. 70). Ecstatic metaphor, at the top of the ladder of metaphorical experience, creates “a sense of presence, a sense of uniting ourselves with something else” (Frye words, as quoted by Bob Denham, p. 72). The free flow of psychic energy is what counts for both. For Bly (at least the early Bly) a true or authentic poem has to involve the “leap” from the conscious, everyday world to the unconscious, universal world. For Frye it’s the gap between subject and object that’s obliterated in ecstatic metaphor. Frye’s is, if anything, a more expansive concept.

Over the years Bly moved deeper and deeper into the study of Jung and Jung’s concept of the unconscious. Throughout the nineties he worked with the Jungian analyst Marion Woodman and in 1998 they published their book The Maiden King. Frye’s interest in Jung was also deep and important. As Bob Denham says, “Frye sometimes expressed anxieties about being considered a Jungian, but he was much more deeply immersed in Jungian thought than is commonly imagined” (Religious Visionary, p. 196). Jung’s Psychology and Alchemy is a rich source for Frye, as Bob Denham wonderfully recounts. “In Anatomy of Criticism, alchemy is seen as a repository of archetypes (rose, stone, elixir, flower, jewel, fire).” (Religious Visionary, p. 194).

Continue reading →