It is of course true that a great deal of trash which passes as literature, or at least as entertaining reading, also articulates social myths with great clarity. I read many of the novels of Horatio Alger at an early age, and as I have a good verbal memory, a journey round my skull would unearth a great many pages of some of the most pedestrian prose on record. I wish very much that a surgical operation could remove it and substitute something better, but still Alger probably did me no permanent damage, as I was never inspired to adopt the virtues of his heroes, and this leads me to hope that the children of today may emerge similarly unscathed from their similar experiences. (“The Developing Imagination”)

The chief difference between the comedy of the Renaissance and of the realistic period is that the resolution of the latter more frequently involves a social promotion, and, like pathos, tends to be an individual achievement. More sophisticated writers of low mimetic comedy often present the same success story with the moral ambiguities that we have found in Aristophanes. In Balzac or Stendhal a clever and ruthless scoundrel may achieve the same kind of success as the virtuous heroes of Samuel Smiles and Horatio Alger. Thus the comic counterpart of the alazon seems to be the clever, likable, unprincipled picaro of the picaresque novel. (“Towards a Theory of Cultural History”; also in Anatomy of Criticism)

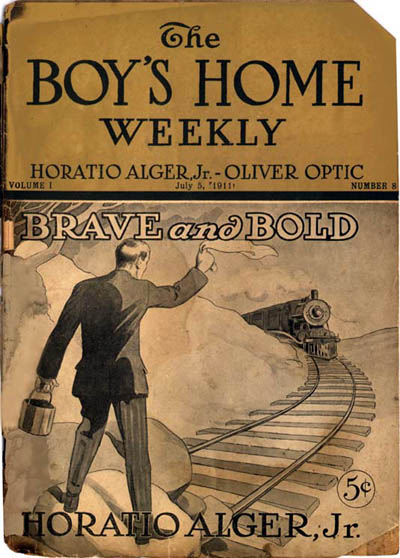

Many people still alive can remember Horatio Alger from their childhood. In Alger there was invariably a boy as hero who started with nothing but the industrious apprentice virtues, and wound up at the end of the story in a steady job earning five dollars a week with a good chance of a raise. Sometimes, if the not very resourceful Alger were hard up for a plot, he attained this by sheer luck, but it was understood that luck comes to the deserving, not to the lucky. Yet already in Alger we are beginning to realize that such fiction can hardly survive the class that produced it, and that that class is on its way out. The kind of entrepreneur capitalism that it helped to rationalize was dead by the First World War, and the fiction died with it. It lingered in the 1920s in the infantilism of Henry Ford and the kind of popular fiction represented by the Saturday Evening Post, and in such moral stampedes as the one that passed the Eighteenth Amendment. But of course the fact that it survived only in such ways showed that it had disappeared into what literary critics call a pastoral myth. Even yet, whenever some people get to the point of emotional confusion at which the feeling “things are not as good as they ought to be” turns into “things are not as good as they used to be,” back comes this fictional image of thrift, hard work, simple living, manly independence, and the like, as the real values of democracy that we have lost and must recapture if, etc. the rest of the sentence depends on whatever is alarming the writer most at the moment. (Introduction to The Stepsure Letters)

In a more recent play, Amadeus, the composer Salieri pleads with God to give him the reward of genius in return for a devout life. God ignores this plea and bestows all the genius on a grubby creep named Mozart. At the bottom of Salieri’s mind was a notion that God would have bourgeois literary tastes, that the central bourgeois fable of the industrious and idle apprentice would be a favourite with him, and that he could always be counted on to enter into a dramatic situation that illustrated it. A glance at the Book of Job might have shown him that the divine mind was not confined in its choice of plots to the formulas of Horatio Alger, but such assumptions die hard, especially when they are not realized to be assumptions. (“The Stage is All the World”)

Even in Shakespearean romance distinctions of rank are rigidly maintained at the end. Bourgeois heroes tend to be on the industrious‑apprentice model, shown in its most primitive form in the boys who arrive at the last pages of Horatio Alger working for five dollars a week with a good chance of a raise. Detective stories often feature an elegant upper-class amateur who is ever so much smarter than the merely professional police; the movies and fiction magazines of two generations ago dealt a good deal with the fabulously rich, the sex novels of our day with lovers capable of prodigies of synchronized orgasm. Here again genuine realism finds its function in parody, as, for instance, The Great Gatsby parodies the “success story,” the romantic convention contemporary with it. (The Secular Scripture)

I have a feeling—probably it’s just one of those would-be profound feelings that it’s comfortable to have—that I cannot really get at the centre of a problem unless something in it goes back to childhood impressions. Thus my New Comedy ideas, the core of everything I did after Blake, probably go back to my [Horatio] Alger reading, and now I think the clue to this labyrinth is the sentimental romance of the l9th century, the roots of which are in Scott. While I lived on Bathurst St. I was constantly reading ghost stories with similar patterns in mind, & Poe & Hawthorne have always been favorites. Underground caves; the Phantom of the Opera, & the like, are all part of the Urthona penseroso pattern. (“Third Book” Notebooks)

One doesn’t realize the immense social prestige of the university until one gets a little outside it. Speaking of them [Bobby Morrison & Beattie], I wonder if the dry rot at the basis of their lives is significant of an economic change in which the bustling, successful, money-making, super-selling young man is no longer a pure clear-eyed Alger hero but an embittered souse. (Diaries, 5 September 1942)