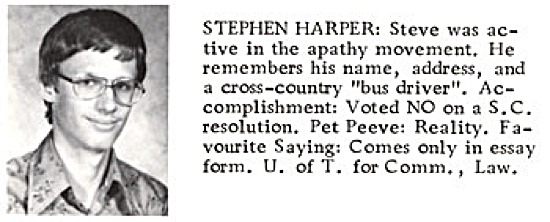

From Vintage Voter via the The Globe and Mail, Stephen Harper’s high school grad photo. Offered without comment.

Monthly Archives: April 2011

Benjamin Disraeli: True Blue Conservative

httpv://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3yrPtRgK6Gk Disraeli addresses Parliament in Mrs. Brown

Benjamin Disraeli died on this date in 1881 (born 1804).

It cannot be said too often: North American politicians who call themselves “conservatives” are no such thing. They are corporatists. Below is some of the notable legislation passed during the arch-conservative Disraeli’s ministry. This is what the record of a real conservative looks like: offering assistance to those in need in the name of social stability; promoting justice for the sake of sound social health. Just the titles of this legislation might give contemporary “conservatives” a Victorian case of the vapors. Where are the tax cuts for the rich and for corporations? Where is the corporate welfare? Disraeli extended the franchise, offered assistance to the poor, and enhanced the rights and protections of workers, including the right to form trades unions:

Artisans’ and Laborers’ Dwellings Improvement Act

Conspiracy and Protection of Property Act

In response to these reforms, Liberal-Labour MP Alexander Macdonald told his constituents in 1879: “The Conservative party have done more for the working classes in five years than the Liberals have in fifty.”

It would raise hurricanes of laughter all along the political spectrum to suggest that today’s “conservatives” might do anything remotely resembling this now.

Maybe a large part of the reason is that Disraeli was extraordinarily accomplished. However “conservatives” regard themselves, glad handing the corporate elite does not round out a world-view.

Here’s Frye making reference in “Dickens and the Comedy of Humours” to Disraeli the novelist; a writer who gives expression to the enduring foundations of romance, despite the conventional thinking:

In general, [it is assumed that] the serious Victorian fiction writers are realistic and the less serious ones are romancers. We expect George Eliot or Trollope to give us a solid and well-rounded realization of the social life, attitudes, and intellectual issues of their time; we expect Disraeli and Bulwer-Lytton, because they are more “romantic,” to give us the same kind of thing in a more flighty and dilettantish way; from the cheaper brands, Marie Corelli or Ouida, we expect nothing but the standard romance formulas. (CW 10, 287)

As Frye goes on to say in his examination of the work of Dickens, the second-tier status of romance is a long way from the truth. Writers of romance like Disraeli are closer to the imaginative bedrock of literature and life than any realist. “Conservatives” who by denying assistance to the poor and justice to society at large to further enrich a bogus crony-capitalisim may flatter themselves as living in “the real world.” But it is in fact not much of a world and, because it’s unsustainable, it is not even real; just temporarily realized and doomed to fail.

Quote of the Day: Canada What?

Primary Concerns, Democracy, and Conservative Ideology

httpv://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jvE9EN4YPGM

The Hour: Stephen Harper and U.S. style media control

Bob Denham`s article on Frye and Kierkegaard, recently published in our journal, shows the importance in Frye’s later work of the Danish philosopher’s emphasis, among other things, on concern. Frye first develops the idea in terms of the tension or dialectic between freedom and the myth of concern, as most fully worked out in The Critical Path. There it is argued that the imagery of literature is ultimately the language of concern. This insight becomes the basis of his later formulation of primary concerns in Words with Power, where he makes the distinction between primary human concerns and secondary or ideological ones. One of the books of Frye`s now famous Ogdoad (famous at least among amateurs of Frye) is entitled Liberal, and it strikes me that this indicates another source of Frye`s concept of concern, and in particular his formulation of the distinction between primary and secondary concerns.

It would be of great interest to examine this idea of primary concerns as a genuine contribution to socio-political thought, specifically liberal and social democratic thought. Certainly there have been essays touching on the liberal humanism of Frye`s critical position, or what I would prefer to call his critical “vision.” It is often a stance he has been attacked for. More sympathetically, Graham Good, for example, has a particularly discerning article on the subject. Years ago I presented at a conference a very preliminary stab at such an examination, but I have not had the opportunity yet to follow it up. Involved in such a study would have to be a comparison, ultimately, of Frye`s concept of primary concerns with such theories as John Rawl’s idea of basic goods, and even more with Amartya Sen and Martha Nussbaum’s idea of basic human capabilities. These ideas are a different way of talking about human rights and are very close to Frye`s primary concerns, focusing as they do on those universal human needs and wishes that can be regarded as essential to the dignity and fulfillment of every human individual. It is worth emphasizing that it is this kind of thinking in the liberal and social democratic tradition that has given us, among other things: universal health care (now severely threatened); legal access to abortion; gay marriage; serious efforts to ensure gender equality and protect minority rights; a less punitive system of law and order aimed at restoring the incarcerated to reentering and contributing to society; a more welcoming policy to refugees fleeing persecution or unimaginable hardship in their own countries. The list could go on.

These great benefits have derived from an often invisible or inarticulate social norm, not in the normative sense, but as an ideal the departure from which makes irony and the grotesque ironic and grotesque. This ideal is “the vision of a more sensible society,” of a world that actually makes human sense. Such a vision works outside literature among individuals in their daily lives and workplaces, giving meaning to their work and actions beyond any need for a pay-cheque. As Frye writes: “one can hardly imagine, say, doctors or social workers unmotivated by some vision of a healthier or freer society than the one they see around them.” The same could be said of any member of society who contributes in a meaningful way, who has, in other words, a social function, this being, as Frye views it, the real significance of the democratic ideal of equality. In a true democracy, everyone is potentially a member of an elite, and no-one`s social function is more worthy of respect than another’s.

This idea of a social vision, ultimately the vision of a world of fulfilled primary concerns, is particularly useful in defining the issues we face in the current Canadian election campaigns. Any genuine social vision of a healthier or freer society is precisely what the program of Stephen Harper and the Conservatives are devoid of. It is telling that Harper almost always speaks of the economy, never of society. It is as if it doesn’t even occur to him. Contrary, however, to the famous tag-line, it’s not the economy, stupid: it’s society.

The Canterbury Tales

httpv://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1knZ65pBRcg

Offered up as a curiosity: an excerpt from the Wife of Bath sequence from Pier Paolo Pasolini’s 1972 film, I racconti di Canterbury. This barely passes as “adaptation,” but it’s gaudy and ridiculous, and maybe those qualities indirectly capture some of the tale’s bawdy spirit. Also, the great Italian actress Laura Betti plays the Wife of Bath — and, as part of the curiosity, Tom Baker, better known as one of the best incarnations of Dr Who, plays one of her husbands

Geoffrey Chaucer recited the Canterbury Tales in the court of Richard II for the first time on this date in 1397.

Here’s Frye’s stark assessment of Chaucer’s Retraction:

Then we find a Retraction at the end, where Chaucer, with a dismally pious snuffle, pleads forgiveness for having written his poetry. Now this is no joke. There is no room in the same poem for both this Retraction and the rest of the work: the most eclectic reader could not extend Chaucer’s moral standards for that. To us The Miller’s Tale is great art and thoroughly good in the Platonic sense of the word: it is the Retraction that appears to us as a grotesquely leering obscenity. It is, of course, customary to invoke the Middle Ages at this point, and say that Chaucer lived at a time when it was generally considered meritorious to make such an exhibition of oneself. But that is far too easy-going. When Chaucer started out he made no concessions to medievalism: he defended his own coarseness by saying that Jesus Himself did not hesitate at coarseness when occasion demanded, and that those who wished to be holier than Jesus could simply read something else. Morally, this defence and its retraction are mutually exclusive. The man who made the Miller, Reeve, Friar, Summoner, and Pardoner was a creator, a worthy servant of the Creator-God who presumably looked, in the Garden of Eden, upon the hinder parts of a she-ape and saw that it was very good. The writer of the Retraction is accepting the moral standards of the Summoner and Pardoner at their face value, with all the hypocrisy and vulgarity they imply. This is something absolutely different from the conclusion of Troilus and Cresyde: there, the great artist rejected the world; here, a canting Worldly Wiseman is rejecting great art. (CW 10, 135)

Frye at the Movies: “The Kid”

httpv://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hURBl5ed9k8

Here’s Chaplin’s first full length feature from 1921.

Be sure to check out our posts on Frye and Chaplin.

TGIF: Charlie Chaplin

httpv://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zskO9O3hF78

It’s Charlie Chapin’s birthday, so the TGIF slot is his.

Just about anything we posted would be worth seeing, but this is still an amazing sequence: the boxing match from City Lights.

Previous posts on Frye and Chaplin here, here, here and here.

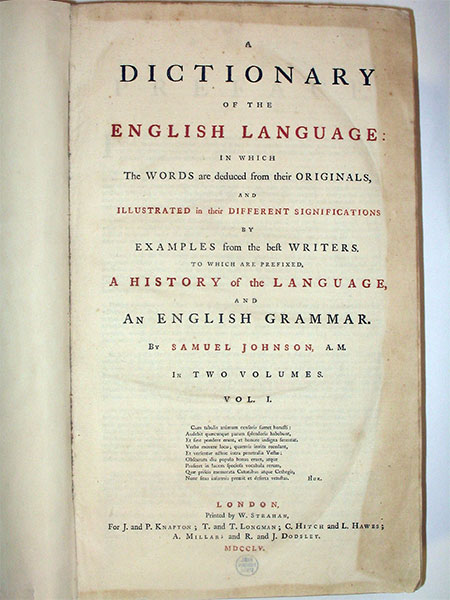

Johnson’s Dictionary

Samuel Johnson published his Dictionary of the English Language on this date in 1755.

Frye in “Rencontre: The General Editor’s Introduction”:

The third in this trio [the other two being Dryden and Swift] of the great age of prose Samuel Johnson, who, thanks to Boswell, is even more famous as a talker than as a writer. This is evidence, if we needed it, that the association of good prose style with good conversation is a social fact, not merely an educational ideal. As we should expect from the author of a dictionary, Johnson has an enormous vocubulary, and his use of it is a further indication of the growing polysyllabic quality of English speech, already mentioned. But though a formidable social figure, and satirized in his own day as “Pomposo,” he is not at all a pompous writer: he consistently directs his reader’s attention to the subject, not to himself. (CW 10, 60-1)

Arnold J. Toynbee

httpv://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aSDYytrYdUw&playnext=1&list=PLB9021297EC5026FD

Arnold Toynbee turns up, in all places, as a character in an episode of Young Indiana Jones, to provide an ominous historical perspective on events in Europe

Today is Arnold Toynbee‘s birthday (1889-1975).

Frye on history, metahistory, myth, and best-sellers in “New Directions from Old”:

We notice that when a historian’s scheme gets to a certain point of comprehensiveness it becomes mythical in shape, and so approaches the poetic in its structure. There are romantic historical myths based on a quest or pilgrimage to a City of God or a classless society; there are comic historical myths of progress through evolution or revolution; there are tragic myths of decline and fall, like the works of Gibbon and Spengler; there are ironic myths of recurrence or casual catastrophe. It is not necessary, of course, for such a myth to be a universal theory of history, but merely for it to be exemplified in whatever history is using it. A Canadian historian, F.H. Underhill, writing on Toynbee, has employed the term “metahistory” for such works. We notice that metahistory, though it usually tends to very long and erudite books, is far more popular than regular history: in fact metahistory is really the form in which most history reaches the general public. It is only the metahistorian, whether Spengler or Toynbee or H.G. Wells or a religious writer using history as his source of exempla, who has much chance of becoming a bestseller. (CW 21, 309)

$50 Billion

The F-35: the jet we don’t need and can’t afford

We’ve entered the stage of the election campaign where there’s always the danger that issues give way completely to optics, the frivolity by which perceptions replace policy.

There’s much that can be said about the Harper government, but perhaps this figure sums it up: $50 billion. That’s the rounded off sum in corporate welfare Harper is proposing to shell out with taxpayer dollars.

Jets: $30 billion.

Jails: $13 billion.

Corporate tax cuts: $6 billion.

We don’t need any of these things, and they will certainly come at the cost of social spending. It’s a guarantee: a Harper majority government, after having squandered a surplus and run up record deficits, will demand “sacrifices” of those already footing the bill for his wish-list.

It’s our money. What law of economics requires that it go to Lockheed Martin and building contractors with Conservative ties and corporations already turning massive profits?

If there must be optics, let this be the filter.