I was intrigued by Jonathan Allan’s description of graduate studies at the University of Toronto. It is probably similar to the experience elsewhere for many students, certainly at McMaster. Clayton’s comments about being in the classroom capture it beautifully: a rhetorical dance, a danse macabre I am afraid, the dance of the death of logic. Little wonder Clayton fled into computer science. His description of it as a rhetorical performance void of argument strikes me as very apt.

At the risk of descending into testimonial, I would like to share my own experience, mid-seventies to mid-eighties, just as the the new critical theories were beginning to take hold. French theory had begun its invasion, and I was then a graduate student, like Jonathan, in Comparative Literature, the “House of High Theory,” as he puts it, at the University of Toronto. Comparative literature departments at the time were the advance-guard of literary theory, particularly deconstruction and post-structuralism. Those were heady days and the new wave moved swiftly, and seductively, and soon broke down the walls of last resistance, English departments, which were of course as much opposed to Frye in many cases as they were to the new theorists (Frye has been controversial from the beginning). At the time, comparative literature students were regarded with great suspicion by professors in English, since we were known to be the hosts, the vectors that threatened the establishment with the disease called deconstruction. But it wasn’t long before many of them succumbed as well, though Toronto, given its conservatism, was certainly the last bastion to fall.

As is usual with such things, the new theorists first protested that they simply wanted the freedom to pursue their own work without prejudice, but once the tide turned it quickly became an imperial enterprise and the tune changed: now that they were the establishment, it was their sacred duty, in the name of the revolution, to ensure that the new approaches become the only work that young scholars be exposed to. By this time post-structuralism had paved the way, via Althusser and Foucault, for New Historicism and the ideologically militant Cultural Studies.

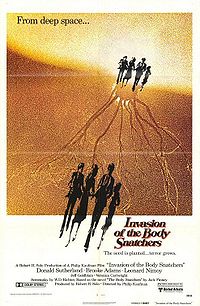

The metaphor that seemed most appropriate to describe this rapid infiltration was a film very popular at the time, Invasion of the Body Snatchers. You’d be talking to someone like a normal person one day, and the next morning there would be a look in his eyes, a strange insistence in his voice, and then you knew: one more pod had made it under someone’s bed. (This, of course, is probably the same feeling many had about the proliferation of Frye aficionados in the fifties and sixties). The rest is history, and it is largely a history of controlling publication decisions, appointments, and grant committees, resulting in the triumphant colonization of English departments across the continent.

As a doctoral student then I was a fervent deconstructionist, and a persecutor of those who tried to resist its tenets. The turning-point came when, a year away from finishing, I had to walk into a classroom and teach: it became quickly clear to me that there was something deeply unsatisfying about demonstrating the “unreadability” or potentially hazardous nature of the works the students were reading. At the time I had never read Frye. My BA was in French and my graduate degrees in Comparative Literature, and as an undergraduate I had the impression that English was a quaint and fusty discipline when compared to the excitements of writers like Baudelaire and Sartre, and so went into French. Near the completion of my doctoral thesis, I was persuaded by a friend that Frye was really worth reading and so I asked him what I should start with. He recommended The Secular Scripture and Fearful Symmetry. It wasn’t but two or three chapters into the former when I felt I had been struck down on the road to Damascus, and by the time I finished Fearful Symmetry there was no going back, not without a great effort of intellectual dishonesty, and however politically wise it might have been for me to do so in terms of my career. I had encountered a mind that transcended any approach to literature that I had come across before, or any that I have met since, and that was that. I hurriedly finished my deconstructionist thesis (an epistemological crisis one chapter away from finishing was the last thing I needed) and, very much like Jonathan, started to read everything Frye had written that I could get my hands on.

The friend, by the way, who recommended Frye’s work to me? Not long afterwards a pod found its way under his bed. He was soon one of the worst detractors of of Frye’s work. He was a Canadianist. I wonder if he was one the people at the conference Jonathan spoke at.

I think it would be fascinating to undertake a history of this period and to account for why critical theory and literary studies took the direction it did. There are always Orc or Oedipal cycles of killing-off- the-fathers, without which, it seems, scholarship would never advance. But the shift in this case was particularly dramatic and perverse, as Jan Gorak suggests, since it represented an entire casting off of assumptions about literature and culture that had existed for generations, and the consequences have been dire: a depressingly incoherent and unsystematic state of scholarship, and the absence of any shared principles or language for engaging literature and culture that are not constantly subject to arbitrary contestation and dispute.

I attended the wedding of my cousin last night, which was held in Hart House at the University of Toronto. My uncle is ninety now, and his oldest friend was there: Ernest Sirluck, the Milton scholar, formerly dean of graduate studies and vice-president at Toronto, and former president of the University of Manitoba. I had the good fortune of being seated beside him at dinner. I asked him about Frye, and about Roy Daniells and Bert Hamilton, and we spoke of that particular generation of the mid-twentieth century, a remarkable one in the history of Canada for the number of important scholars and thinkers it produced. We spoke of the shift that had taken place in literary scholarship, and of signs that the hegemony of post-structuralism and cultural studies might be weakening significantly. But then he said, with a certain emotion: the damage done has been enormous, and even if the fever lifts, is there any hope that the patient will ever fully recover?

More specifically, as to the rejection of Frye and his work, beyond his stature as one of the most eminent or the great white fathers, I think it is Merv Nicholson who has insisted that it can only be something deeply threatening in Frye’s way of thinking about literature that makes for the kind of resistance he has met with from a certain quarter from the beginning. Whatever that is, it is probably the same thing that explains the instances of a very different kind of response to Frye’s work: as Jonathan’s post, and Trevor’s earlier one make clear, reading Frye can transform the way we think not just about literature but the world, leaving whatever book of his we happen to be reading sitting “in pieces, the spine broken, the margins marked up.”

I remember a while ago Michael Happy and I were having a coffee together, and he had with him his copy of Words with Power (I think it was) that he was reading at the time. I picked it up and after flipping through the pages, I asked him: “why don’t you just underline the sentences you DON”T think are important?”

Is the link to Jonathan Allan’s description this one: http://fryeblog.blog.lib.mcmaster.ca/2009/09/26/jonathan-allen-finding-frye/ ?

If I click on description above, I get asked to log on to wordpress at McMaster.

BTW – that post and yours are both interesting.