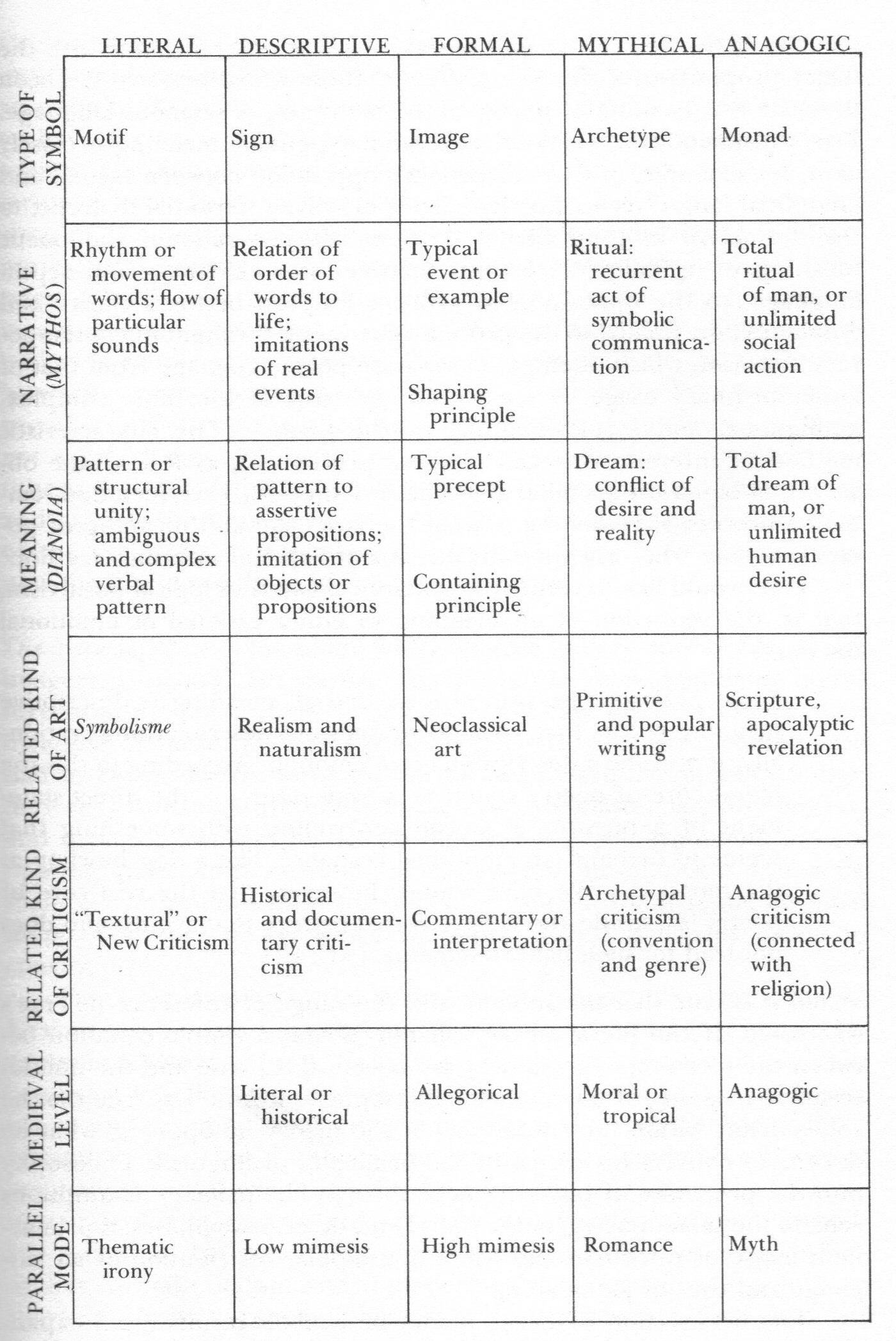

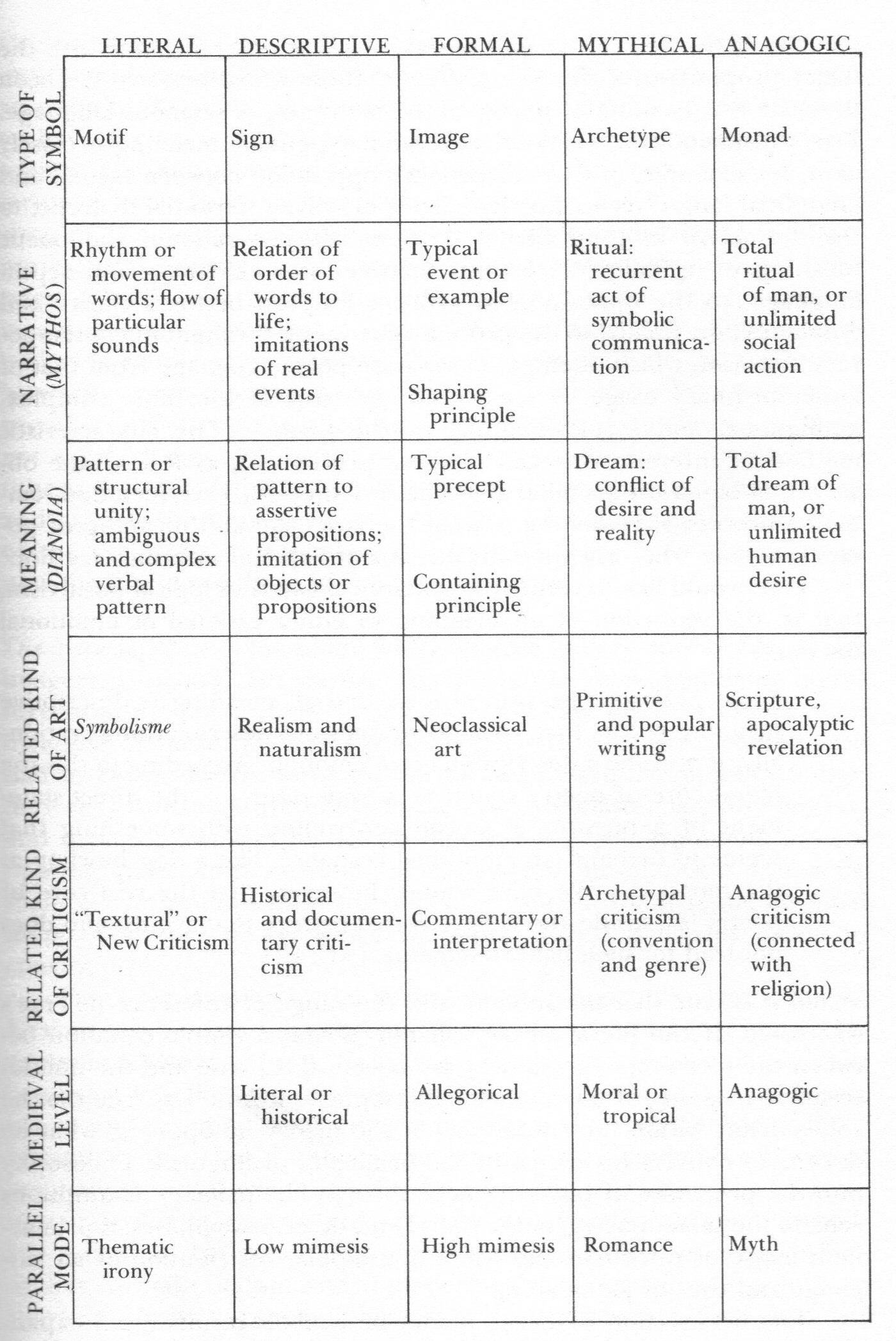

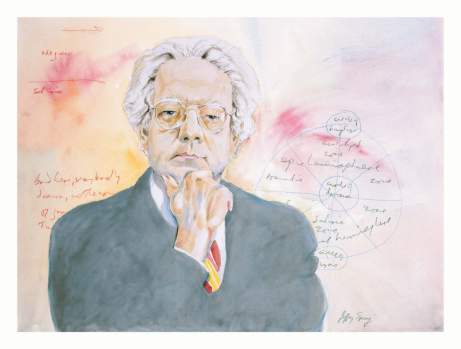

Further to the ongoing discussion on archetype, here is a chart I put together about 40 years ago:

Further to the ongoing discussion on archetype, here is a chart I put together about 40 years ago:

Responding to Russell Perkin:

In the Prologue to his 1949 diary, Frye writes, “I’m beginning to feel a bit restless—impatient with Victoria’s corniness, & wondering if it is really the best place in the world to work” (Diaries, 53) Then there are these entries:

The English department [at Michigan State] however lives in a squalor that reminded me of Victoria College. (Diaries, 193––26 April 1949)

Well, well. On the way back Woodhouse told me Don Cameron Allen of Johns Hopkins had written him asking him if he thought anyone in Canada was capable of filling a full professorship there: 19th c. preferred, but failing that, history of criticism & general problems. At the end of his letter he said “What about Frye?” I said “please don’t slam that door.” Salary $7000, leading (they don’t say how soon) to $8000. (Diaries, 231––16 January 1950)

At the moment, of course, I feel dreadfully bored because two things dangling in front of me all month like the apples of Tantalus haven’t moved any closer. One is the Johns Hopkins offer, the other the English invitation [NF had been invited by Bonamy Dobrée to lecture in England]. I’ve more or less written off the former, & the latter is fading. Then again, by not applying for the Nuffield I’ve stuck my neck out on the Guggenheim, & if I miss it I’ve really had it. Oh, well, I suppose I should set all this down, as I have at least another month of it to go through. More important is my recurring restlessness about Victoria, wondering if they’ll really adopt [Walter T.] Brown’s policy of running it at a third-rate level. If so, I must make up my mind to leave, & that won’t be easy. As I’ve said, I don’t think much of Joe as the next head, but he couldn’t be much worse than Robins has been lately. Well, that’s enough ego-squalling for the present. Light—I mean Lead, kindly Light, amid the encircling gloom. I don’t care about choosing my path, but I’d like to get a glimpse of it occasionally. (Diaries, 242––27 January 1950)

After the usual buggering I went into lunch with the males in the English department, Cecil Bald, & Bennett. I had mildly suggested moving the party to Chez Paris [Paree], in view of the fact that Bald has a special interest in Coleridge & it was silly to leave Kay Coburn out. Robins said he couldn’t make the switch because Bennett didn’t want to take the party “off the campus.” [NF had suggested that the group have lunch “off the campus” so that Kathleen Coburn could be included in the party. Women were excluded from eating in the Senior Common Room until 1968] That’s the kind of thing that makes me restless about staying at Victoria. (Diaries, 248–9––3 February 1950)

Responding to Clayton Chrusch:

Here’s Frye’s extended definition of “Archetype” from the Harper Handbook to Literature:

Archetype. A term that has come down from Neo-Platonic times, and has usually meant a standard, pattern, or model. It has been sporadically employed in this sense in literary criticism down to at least the eighteenth century. An archetype differs from a prototype (even though the two words have often been used interchangeably) in that prototype refers primarily to a genetic and temporal pattern of relationship. In modern literary criticism archetype means a recurring or repeating unit, normally an image, which indicates that a poet is following a certain convention or working in a certain GENRE. For example, the PASTORAL ELEGY is a convention, descending from ritual laments over dying gods, and hence when Milton contributes Lycidas to a volume of memorial poems to an acquaintance who was drowned in the Irish Sea, the poem is written as a pastoral elegy, and consequently employs a number of conventional images that had been used earlier by Theocritus, Virgil, and many RENAISSANCE poets. The conventions include imagery of the solar and seasonal cycles, in which autumn frost, the image of premature death, and sunset in the western ocean are prominent; the idea that the subject of the elegy was a shepherd with a recognized pastoral name and an intimate friend of the poet; a satirical passage on the state of the church, with implied puns on pastor and flock (naturally a post-Virgilian feature); and death and rebirth imagery attached to the cycle of water, symbolized by the legend of Alpheus, the river and river god that went underground in Greece and surfaced again in Sicily in order to join the fountain and fountain nymph Arethusa.

One of the conventional images employed in the pastoral elegy is that of the red or purple flower that is said to have obtained its colour from the shed blood of the dying god. Lycidas contains a reference to “that sanguine flower inscrib’d with woe” [l. 106], the hyacinth, thought to have obtained red markings resembling the Greek word ai (“alas”), when Hyacinthus was accidentally killed by Apollo. Milton could of course just as easily have left out this line: the fact that he included it emphasizes the conventionalizing element in the poem, but criticism that takes account of archetypes is not mere “spotting” of such an image. The critical question concerns the context: what does such an image mean by being where it is? The convention of pastoral elegy continues past Milton to Shelley [Adonais], Arnold [The Scholar Gypsy], and Whitman’s When Lilacs Last in Dooryard Bloom’d. Here again are many of the conventional pastoral images, including the purple lilacs: this fact is all the more interesting in that Whitman regarded himself as an antiarchetypal poet, interested in new themes as more appropriate to a new world. In any case the gathering or clustering of pastoral archetypes in his poem indicates to the critic the context within literature that the poem belongs to.

The archetype, as a critical term, has no Platonic associations with a form or idea that embodies itself imperfectly in actual poems: it owes its importance to the fact that in literature everything is new and unique from one point of view, and to the reappearance of what has always been there, from another. The former aspect compels the reader to focus on the distinctive context of each particular poem; the latter indicates that it is recognizable as literature. In other genres there are other types of archetypes: a certain type of character, for example, may run through all drama, like the braggart soldier, who with variations has been a comic figure since Aristophanes’ Acharnians, the first extant comedy. The appearance of a braggart soldier in a comedy by Shakespeare or Molière or O’Casey is quite different each time, but the archetypal basis of the character is as essential as a skeleton is to the performing actor. Thus the archetype is a manifestation of the extraordinary allusiveness of literature: the fact, for example, that all wars in literature gain poetic resonance by being associated with the Trojan War.

In JUNGIAN CRITICISM the term archetype is used mainly to describe certain characters and images that appear in the dreams of patients but have their counterparts in literature, in the symbolism of alchemy, in various religious myths. The difference between psychological and literary treatments of archetypes is that in psychology their central context is a private dream. Hence they tell us nothing except that they appear, once we leave the psychological field of dream interpretation. The dream is not primarily a structure of communication: its meaning is normally unknown to the dreamer. The literary archetype, on the other hand, is first of all a unit of communication: primitive literature, for example, is highly conventionalized, featuring formulaic units and other indications of an effort to communicate with the least possible obstruction. In more complex literature the archetype tells the critic primarily that this kind of thing has often been done before, if never quite in this way.

With regard to Joe’s question about Frye’s method and the “way he thinks,” it seems to me that a critical method is a function of at least four variables: the language a critic uses (the material cause: out of what?); the subject matter he or she explores (the formal cause: what?), the manner used to make a point or construct an argument (the efficient cause: how?), and the purpose(s) of his or her discourse (the final cause: why?). With regard to Frye, all of these variables are worth sustained investigation.

Consider the efficient cause. How does Frye proceed in setting out his position on whatever his subject matter is? We might approach this by asking, How does Frye’s mind work? How does he think?

1. Dialectically, by the juxtaposition of opposing categories. There are scores of these: knowledge and experience, space and time, stasis and movement, the individual and society, tradition and innovation, Platonic synthesis and Aristotelian analysis, engagement and detachment, freedom and concern, mythos and dianoia, the world and the grain of sand, immanence and transcendence, ascent and descent, and so on. Consider the chapter titles of part 1 of Words with Power: sequence and mode, concern and myth, identity and metaphor, spirit and symbol.

2. Epiphanically. Intuitive moments of sudden illumination. Frye records seven or eight of these, some of them named: the Seattle illumination, the St. Clair epiphany. These might not properly be called thinking, but these moments were important in forming the vision that he writes about.

3. Schematically. Frye can’t think without a diagram in his head. Spatial representation of thought (diagrams, charts, categories arranged in space––cycles, circles, tables, and other visual taxonomies) are always prior. His diagram of diagrams he called “The Great Doodle.” Lesser doodles (his phrase) include the omnipresent HEAP scheme and the ogdoad. The hundreds of schema he uses are stored (for instant recall) in his vast memory theater. Thinking schematically means that he is fundamentally a deductive thinker (in spite of the fact that I can think of no critic who had a greater inductive store of literary data).

4. Analogically. Frye is obsessed with similarities rather than differences. He does, of course, have a strong Aristotelian streak, what with all his anatomizing and categorizing. But while he agrees with Coleridge that we can distinguish where we cannot divide, the bottom line is that Frye is an analogical thinker, like Plato.

5. Upwardly. Frye is always moving toward a telos, an end. There is always another step to be taken to get beyond the present mental or imaginative state. “Beyond” is the most revealing preposition in Frye’s religious quest––a preposition that takes on special significance only late in his career. During the last decade of his life he uses the word repeatedly as both a spatial and a temporal metaphor. Having arrived at a particular point in his speculative journey, over and over he reaches for something that lies beyond. Notebook 27 (1985) begins with a series of speculations about getting to a plane of both myth and metaphor beyond the poetic, and Frye even confesses that there is no reason at all to write Words with Power unless he can get to that plane (LN, 1:67). The Bible implies that there is a structure beyond the hypothetical (LN, 1:8, 14). Many things are said to be beyond words: icons, certain experiences, the identity of participation mystique (LN, 1:15, 16). Here’s a sampler:

A footnote to Clayton Chrusch’s “The Hermeneutics of Charity,” drawn from some paragraphs on love I wrote about elsewhere.

The genuine Christianity that has survived its appalling historical record was founded on charity, and charity is invariably linked to an imaginative conception of language, whether consciously or unconsciously. Paul makes it clear that the language of charity is spiritual language, and that spiritual language is metaphorical, founded on the metaphorical paradox that we live in Christ and that Christ lives in us (The Double Vision, 17).

The various principles that are the foundation of Frye’s concept of identity (metaphor, kerygma, possession, the fourth awareness, higher consciousness) should lead us, he says, to “myths to live by.” But what are these existential myths that come from “the other side” of the imaginative? What are the “coherent lifestyles” that Frye’s hopes “will emerge from the infinite possibilities of myth”? (Words with Power, 143). Although he often appears hesitant to give a direct answer to these questions, preferring to assume the role of Moses on Mount Pisgah, the answer does surface in the conclusions of his last three books where the gospel of love becomes the focus of his discussion.

Frye’s speculations on love begin early. In Notebook 3 (1946–48) he probes the meaning of love in different contexts: his own erotic and fantasy life, his attitude toward the Church, his reflections on yoga and on time. Here are two representative reflections:

Joachim of Floris has a hint of an order of things in which the monastery takes over the church & the world. That is the expanded secular monastery I want: I want the grace of Castiglione as well as the grace of Luther, a graceful as well as a gracious God, and I want all men & women to enter the Abbey of Theleme where instead of poverty, chastity and obedience they will find richness, love and fay ce que vouldras; for what the Bodhisattva wills to do is good. (Northrop Frye’s Notebooks and Lectures on the Bible and Other Religious Texts, 17)

Each dimension of time breeds fear: the past, despair & hopelessness & the sense of an irrevocable too late: the present, panic & sense of a clock steadily ticking; the future, an unknown mystery gradually assuming the lineaments of the consequences of our own acts. Hope is the virtue of the past, the eternal sense that maybe next time we’ll do better. The projection of this into the future is faith, the substance of things hoped for. Love belongs to the present, & is the only force able to cast out fear. If a thing loves it is infinite, Blake said, & the act of love is itself a vision of a timeless world. (ibid., 59)

Frye’s speculations on love reappear some thirty-five years later in the conclusion of The Great Code, where he probes the meaning of the Word of God in the context of Biblical language. This language, Frye says, is enduring, inclusive, welcoming, and beyond argument, and it can move us toward freedom and beyond the anxiety structures created by the human and divine antithesis (231–2). The Great Code, however, provides little concrete guidance about the function of love in the myths we are to live by, though the notebooks for The Great Code contain numerous entries on “the rule of charity.” But during the eight years following The Great Code Frye devoted a good deal of energy to working out the implication of the language of love. In Notebook 46 (mid- to late 1980s) he writes, “Love is the only virtue there is, but like everything else connected with creativity and imagination, there is something decentralized about it. We love those closest to us, Jesus’ ‘neighbors,’ people we’re specifically connected with in charity. For those at a distance we feel rather tolerance or good will, the feeling announced at the Incarnation” (Late Notebooks, 2:696). This “only virtue” idea gets developed in Words with Power where love, Paul’s agape or caritas is said to be “the only genuine form of human society, the spiritual kingdom of Jesus” (89).

Responding to Michael Happy:

It’s not so clear to me that Frye has been “excluded from” critical discourse or that he has been “effectively excised from the critical canon.” He still makes his way into the anthologies of criticism. His books continue to be translated abroad (115 translations in 25 languages). Students continue to write dissertations and theses about his work: there are 229 doctoral dissertations in which Frye’s work figures importantly, 194 of which have been written since 1980. And people continue to write essays and books about his work. There are 42 books devoted to their entirety to Frye, seventeen of which have been written in this century (thirty have appeared since 1990). In Northrop Frye: An Annotated Bibliography (1987), I listed 588 essays and book chapters devoted to Frye, covering the first fifty six years of his writing career. Since that time another 1320 have appeared. In other words, 56% the essays about Frye have appeared during the past twenty two years. The Great Code, written after the alleged Golden Age, elicited 189 reviews. Somebody out there is reading Frye.

Alan Adamson has pointed out that director Mary Harron is the daughter of Don Harron, establishing a link between Frye and American Psycho.

I suppose by this logic, we’ve also got a link to Stephen Vicinczey’s In Praise of Older Women (novel by second husband of Mary Harron’s mother). If, as Frye says (following Whitehead) that “everything is everywhere at once,” then we won’t be disappointed in finding links.

Frye, incidentally, wrote a dust jacket blurb for Vizinczey’s erotic novel, the request for which rather mortified Mary Harron’s mother–Gloria Fisher Harron Vizinczey.

In the course of editing Frye’s Diaries––more than a decade ago now––I sought to identify the more than 1,200 people whose names crop up in the diary entries. I corresponded with a number of these people, most of whom were his students at Victoria College in the 1940s and 1950s. To take one year as an example, I wrote to seventy‑eight people who made an appearance in the 1949 diary: fifty‑nine responded. I would ordinarily inquire of all those I wrote whether they remembered the occasion mentioned by Frye, and I would usually invite them to provide some biographical information about themselves and to share their memories of Frye as a person and teacher. I often requested the correspondents to help identify others mentioned in the diaries. I was interested in learning specific details in order to annotate the Diaries, but my invitation to the correspondents to reflect on their experiences with Frye and on the Victoria College scene at the time would help me, I hoped, to reconstruct the social landscape on campus during the seven years covered in the Diaries. The correspondents were generous in their responses. The more than one hundred replies I received, many quite extensive, provide a rather remarkable body of reminiscence.

One leitmotif that runs throughout the letters I received is the power and generous presence that Frye had as a teacher. Here is a sampler of the correspondents’ tributes:

• Northrop Frye was the greatest single influence in my life. (Phyllis Thompson)

• My own memories of Frye are filled with respect and gratitude. What incredible luck to have been “brought up” by him! I remember the excitement of his first lecture every fall. There was a ping of the mind, like a finger snapped against cut glass. You came back from your grungy summer job and then there it was, the whole intellectual world snapped into life again, the current flowing. (Eleanor Morgan)

• I still cannot believe my good fortune in having been taught so many stimulating courses by a person of such brilliance and compassion. His ideas were electrifying, encyclopedic, and revolutionary. . . . Each year when I returned to the university, the hinges of my mind sprang open, and my brain pulsed with the excitement of Frye’s thinking, his eloquence, and his wit. But what keeps his influence on my life vivid and profound to this day is that he enabled us to translate the leaps of intellect we experienced in his lectures into the emotional underpinnings of a way to look at the world and one’s place in it––in short, to be in the world, yet not of it. (Beth Lerbinger)

• Frye would lecture without notes, yet the class rarely turned haphazard. He asked questions constantly that required a knowledge not only of the Bible and classical mythology, but also of the major works in English and American literature. No one could keep pace with all the references, but still the effect was to illuminate and give a structure to a rich and fascinating verbal universe. And then, as an added bonus, just when you thought he had reached the conclusion his investigation was leading to, he would use that “conclusion” as the opening position in a new line of investigation. (Ed Kleiman)

• In short, the Frye course [Religious Knowledge] in one way made for a lot of fun at home. In another way it changed our lives forever. (M.L. Knight)

Some years ago one of Frye’s former students, Don Harron, sent me a copy of My Frye, His Blake, saying that it had been rejected by a university press because it was not academic enough. Harron’s summary of Frye’s Fearful Symmetry, however, was intended not for an academic audience but for the common reader. Harron calls his 279‑page summary a down‑sizing of Frye’s complicated and sometime difficult exposition of Blake’s prophecies. My Frye, His Blake is an abridgement of Fearful Symmetry. It is not so much an effort to simplify Frye as to make him more accessible to the nonspecialist by presenting, in Pound’s phrase, the “gists and piths” of Frye’s book––a concentrated form of its argument, combining his own summaries with Frye’s words. I’m hopeful that it might yet find a publisher.

Here’s Harron’s preface:

BEFORE BEGINNING

To deal first with that somewhat presumptuous and proprietary title: I am one of Northrop Frye’s former students, but can lay no special claim to him. Like James Hilton’s fictional “Mr. Chips,” he and his wife Helen remained childless throughout their lives, but bred thousands of devoted, surrogate progeny like myself, who considered them both as role models during that green island in our lives we call college days.

I was heartened by the announcement that all of Frye’s literary output is to be re-issued in a thirty‑volume collection. At the same time I worried that his legacy might be confined to academic circles, and miss the larger public he freely sought during his lifetime. This attempt of mine to summarize the first of his many books may be construed by some as a kind of Blake for Dummies, but that is not my intention.

The origin of My Frye, His Blake stems from the first essay I ever wrote for the great man back in 1946. I forget the subject of my paper, but I will never forget the mark he gave me. It was a C‑minus. He added the words: “This is mostly B.S. , but you do have a gift for making complex ideas simple.” The latter half of that cryptic statement is the reason for this book.

I was a freshman at Victoria College, University of Toronto, in 1942, but since I was enrolled in a course known as Sock and Fill (Social and Philosophical studies), I didn’t have any lectures with Northrop Frye that first year. It was months before I got to hear him in a public lecture on “Satire: Theory and Practice.” I sat beside two nuns from St. Michael’s College who rocked back and forth with delight as Frye quoted Pope and Swift and Dr. Johnson and added more than a few ripostes of his own. They nearly rolled in the aisle when he quoted Dante reaching the dead center of evil and passing through the arse of the Devil to the shores of Purgatory.

When I returned to Vic in 1945 after two years’ undistinguished service in the RCAF, it was general campus knowledge that the book Northrop Frye had been thinking about and writing for more than ten years was on the English poet and engraver William Blake (1757–1827). Fearful Symmetry is considered by many to be the most complex of Frye’s writings. It was his second book, the Anatomy of Criticism written ten years later, that gave him his international reputation as a literary critic. When I took courses with him in Spenser and Milton during my undergraduate years 1945–48, he was in the throes of preparing the Anatomy, and a good deal of that book came out in his lectures to us.

Frye appears in "The Pajusnaya Consignment" (above, July 1984) in Marvel's New Defenders series

In addition to Amis’s The Rachel Papers Frye has made his way into a number of poems, plays, novels, and discursive texts. An earlier post catalogued his appearance in contemporary poems. As for the other genres, one of the central characters of David Lodge’s Changing Places (1974) refers humorously to the perpetual motion of an elevator, “a profoundly poetic machine,” as symbolizing Frye’s theory of modes in Anatomy of Criticism (London: Seeker & Warburg, 1975; Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1978), 212–13. Professor Kingfisher in Lodge’s Small World (1985), a sequel to Changing Places, is a fictionalized version of Frye. In Thomas King’s Green Grass, Running Water Dr. Joseph Hovaugh is modeled on Frye. Here are further examples:

• The following bit of dialogue occurs in Frederic Raphael’s play, Oxbridge Blues, from Oxbridge Blues and Other Plays for Television (London: BBC, 1984). Victor is a serious writer. Wendy is his wife:

Victor: I didn’t think you felt like discussing it.

Wendy: I don’t even know what “it” is. What is it? I know you’re ridiculously jealous of Pip and you can’t even bring yourself to accept his generosity without looking as though you’d much sooner be reading the collected works of — of — of — oh — Northrop Frye.

Victor: I would. Much. The Anatomy of Criticism, though flawed, was a seminal work in some ways. Why did you happen to choose that name?

Wendy: I wanted someone with a silly name.

Victor: I don’t find Northrop particular silly.

Wendy: Well I do. I find it very silly indeed. Not as silly as you’re being, but still very silly.

• From Gail Godwin’s The Odd Woman (New York: Knopf, 1974), 257–8:

Was Gabriel’s project quixotic? For almost two years, she had vacillated between thinking him a nearsighted fool and a farsighted genius. How could she tell? Surely there must be a way to measure it, but how? After the fact, it became a bit simpler. For instance, in the field of literature, of literary criticism, she knew Northrop Frye was a genius—even though some respectable scholars like Sonia Mark’s husband detested Northrop Frye. Frye’s ideas made sense; they rested on valuable hypotheses; they lit up the entire realm of literature for you. After you had read Frye, you thought of your favorite books as parts of a large family. You not only saw them as you had before, but you saw behind them and in front of them. It was like meeting someone, forming an opinion about this person, then being privileged to meet the person’s parents and grandparents, as well; and then being privileged to meet the person’s children, and grandchildren! Of course, someone like Max Covington would say, The person himself, alone, should be judged. What do parents have to do with it? What do his children have to do with it? They only confuse and diffuse you from the proper study of the object, which is: the object itself.

She had tried to lift her assurance about Frye—as one might gingerly try to lift an anchovy from its tin and place it, undamaged, on a plate—and transfer it toward her wavering confidence in Gabriel. Surely, during the forties and fifties when Frye was painstakingly filling his wife’s shoe boxes with notecards for Anatomy of Criticism, Mrs. Frye had had an occasional qualm. Or had she? After all, Frye had done Fearful Symmetry first. She had that to build on. She knew that her first closetful of shoeboxes had come to something. Whereas, with Gabriel, there was only the queer, eccentric little monograph, published half a lifetime ago!