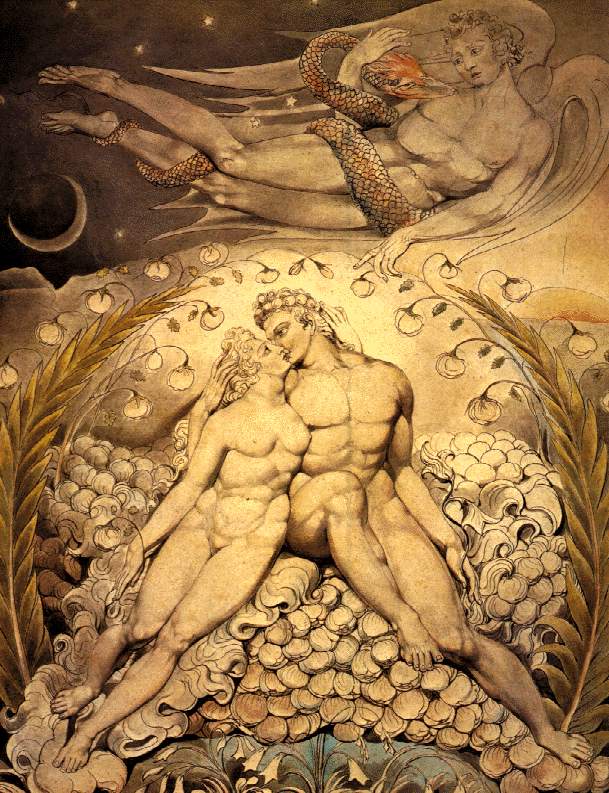

Blake's Nebuchadnezzar

Northrop Frye letter to Roy Daniells, 20 December 1973:

It seems to me that there are two mental processes which are quite distinct, both called belief. One is the existence of evidence which seems conclusive, as when I believe that the earth goes round the sun and not vice versa. The other is a belief derived not from evidence, but from imaginative vision. A belief of this kind is an axiom of one’s conduct: what a man believes in this sense is only what his actions show that he believes. Such beliefs represent a voluntary choice from an infinite number of imaginative possibilities. The gospels present their story as a myth, an imaginative vision. They are remarkably careless about collecting or appealing to evidence in the form of testimony or reason. The account of the resurrection is designed to elicit the response “I can believe in a conquest over death achieved by human, backed by divine, power,” or something like that. I don’t think they are trying to elicit the response “I find that these things happened exactly as described, because I believe that the writers are trustworthy historians.” They are not trustworthy historians: they tell four different stories. But they are all agreed that resurrection is an important subject to decide on for belief, one way or the other. From this point of view, it is not necessarily a misleading myth to say “in Adam all die,” which simply means that everybody dies.

I agree about the habitual dishonesty of theologians, but of course they are just as confused as everyone else about the distinction between the two kinds of belief. As long as they could they tried to insist that belief in Christ was the same kind of belief as belief in the global shape of the earth. Forced out of that position, they find themselves with no standards for any other kind of belief. Very few theologians know or care much about literature or about the mental processes it calls for. So they cannot understand that the gospel writers wrote in mythical rather than historical language because they felt that what they had to say was too important to be trusted to factual language.

Northrop Frye letter to Roy Daniells, 19 March 1975

What fills me with horror and terror, to use your words, is the mystery of the corrupted human will. That is never more corrupt than when it gets to work in the religious area, in obedience to Swift’s principle that we use religion to hate each other and not for love. The desire to persecute is never founded on “believe in God,” but always on “believe in what I mean by God”––all persecution and inquisition have been products of man’s deifying of his own understanding. That and the lust for political power. In the Apocalypse of Peter, one of the earliest NT pseudepigrapha, Peter is shown hell, given a strong hint that the sufferings there may not be everlasting after all, and then cautioned not to say this to anyone when he gets back, because people won’t behave properly unless they’re threatened with this kind of bogie. That’s the way social institutions operate, and they operate in the same way even in Marxist countries where there’s no religious basis as such. They all try to paralyze man with fear.

Christianity makes a good deal of sense to me because its myth does. It identifies man and God in a way that doesn’t cripple our critical faculties, and the kind of man it sees as divine is a man who cared enough about what was happening to other men to go through a pretty grim death. I know that the Christian myth has been treated as fact but the people who did that were repeating the crucifixion when they made martyrs of people like Bruno and Servetus.