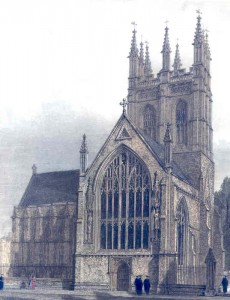

Merton College Chapel

Rodney Baine, mentioned in the 1950 diary entry for 23 August, was a U.S. Rhodes Scholar studying at Oxford, whom Frye met during his early days at Merton College in 1936 –– one of several fellow students he chummed around with. Other friends were Joseph Reid from Manitoba, Alba Warren from Texas, Charles Bell from Mississippi (all Rhodes Scholars) and a hard‑drinking New Zealander, Mike Joseph. In 1937 Frye spent time between terms touring Italy with Baine and Joseph and once back in Oxford he took up residence in a boarding house some distance from Merton College, sharing a suite with Baine and Joseph. Frye apparently had not seen Baine between their Oxford days and the 1950 chance encounter on Massachusetts Avenue in Cambridge, where Frye was studying during his Guggenheim year. After stints at MIT, the University of Richmond, and Delta State University of Alabama at Montevallo, Baine landed a teaching position in 1962 at the University of Georgia, where he became a distinguished eighteenth‑century scholar. Among his publications were books on on William Blake, Daniel Defoe, Robert Munford, and James Oglethorpe. In 1981 Baine’s son James established the Rodney M. Baine Lecture Fund to commemorate his father, and in April 1982 Frye presented the Rodney Baine Lecture, “An Illustrated Lecture of Blake’s Jerusalem” at the University of Georgia. Baine died in 2000.

In the full diary entry for 23 August 1950 Frye wrote, “Evidently he [Baine] was closely involved in the Charlie-Mildred bust up: in fact he had a hand in drawing up the articles of separation, & is still friendly & still corresponds with both. He says that when we saw them they probably weren’t even living together, as Mildred had kicked him out of the house soon after he got back from Italy.” The reference is to the divorce of Charlie Bell and Mildred Winfree, with whom he had lived during his year at Oxford. Frye adds: “Charlie’s present wife [Diana (Danny) Mason] is a Quaker, & he reports that he has had the happiest year of his life. Bell later taught at Princeton, the University of Chicago, and St. John’s College in both Annapolis and Santa Fe. Several years back Charlie Bell sent me his reminiscences about Frye from the time of their Oxford years. I reproduce it here, with editorial insertions in square brackets:

The Imprint of Northrop Frye in Charles Bell’s Poetic Now

In recollection what counts is honesty. What that means here is not to attempt what I cannot do. Since Oxford, I have been with Norrie Frye only twice; and our between-war studies and travels are past more than forty years. All I have are my journals and shadowy thoughts. These can only evoke the scholarly balance of Frye through the romantic self-absorption of Bell.

Yet from the first meeting, Norrie has been a presence in my life. How can that be, under the divergent independence we have pursued––he in the recognition and honor of a scholarly home, I through the departmental exile of half-published obscurity? By a neglected first rule of philosophy, if a thing is, it is possible.

My Oxford Journal records the meeting (March 1, 1937):

We arrived at Rodney Baine’s (Merton) in time for tea. He had invited also Frye, an American (sic) and some other man (Mike Joseph), both of whom are planning a trip to Italy for the Easter Vacation. We wanted to discuss our plans and see what the chances are of our going together. Happily, we all want to do about the same things, so we may be in company most of the time.

The laconic journal says nothing of his appearance, his ideas, his intensity; nothing of what we shared: the Oxford dream island of liberal Europe; the crisis of that world, Hitler and Stalin reaching through Spain toward the war many conceived as ending civilization; our search through thought, literature, and the arts for visionary renewal.

True, after the Italian trip and by the end of the Spring Term, in explaining to my father my preference for overseas friends (“the British lads seem to us to linger in emotional and intellectual adolescence”), I specified:

The people I like and admire, Norrie Frye, [Mike] Joseph, Rodney [Baine], Lou [Palmer], and the rest, turn out to be colonials of some sort. Norrie is one man whom I could follow almost as a disciple. He is as near a genius as anyone I have known.

Could that discipleship for one older and wiser, prevent the species differentiation of a romantic brought up in the paradox-dregs of Civil War Mississippi –– Frye’s ground the glacial rock of the Canadian shield, mine the burnt-off plantation clearings in a Delta swamp, the mould, dry-rot and fire of Faulkner’s South? His scholarship was transcending and translating a ministerial calling; my Faustian need was stretching me between Promethean science and a neo-Augustinian and Spenglerian converse.

What we should most have discussed was the Blake of his early and later thought:

The first person in the modern world who understood that the older mythological construct had collapsed was William Blake. He also . . . set up the model for all the nineteenth-century constructs . . . where cultural values float on a perilous sea. (Creation and Recreation, 1980 [55])

It was Blake I had been drawn to almost from childhood. On the freighter from New Orleans to London I had pursued three books. The first was Wolfe’s Look Homeward, Angel, which I walled in and despised:

It takes a week of Chaucer, Shakespeare, Bach, and Botticelli, to stem the maudlin nostalgia of that refrain “O lost, and by the wind grieved, ghost, come back again.”

The second was Shakespeare, my restorer to an age of tragic joy. In the twenty-three days at sea, I read or rearead most of the plays. The third was Blake, in whom Wolfe’s Ulro despair was vortexed into vision by a storm almost as energized as that of King Lear.

It was Blake as much as anyone who would call me from the physics I was elected to study, through English, the only cultural discipline I could manage to read, to a life-poesis of meaning, from Satanic Math to Symbolic History [Bell’s multimedia, videocassette series on cultural history]. And it was with The Marriage of Heaven and Hell and Visions of the Daughters of Albion that I had made the experiment that fall and winter (1936-37) or rereading, even to memorization, until what had seemed insoluble (no Blake Dictionary in those days) took on the simultaneity of the prophetic states which would polarize and integrate my organic thought and life. We must all have known (by 1938), that Frye was shaping the doctoral thesis which would engender Fearful Symmetry; but I swatted away at Blake in solitude, as if one couldn’t learn anything from anybody anyway. It was more than thirty years later that I would send Norrie a slide lecture where the merging one-many of contrasting states––Albion, Orc, Luvah, Christ, Lucifer, Satan, Urizen, even Los, Job, Blake––was tied to the visible modifications of the arm-flung gesture: liberating joy, crucifixion, weary acceptance, the down-turned curse of the boil-smiting fiend (like Oothoon’s preying eagle out of the wing-lifted eagle of inspiration); to receive his astonished reply:

I had no idea that you were so interested in Blake . . . or had such command of his symbolism and knowledge of his text.

What Frye had begun to give me from the first was not specific answers, but the companionable looming which affirmed shared responsibilities.

I found my way to Italy alone. It was in Rome that Norrie and the rest overhauled me. Since my journals deal mostly with art and the opinions are consistently for early-cycle Egyptian, early Greek, medieval; consistently against New Kingdom Egypt, Rome, Baroque, or modern, Norrie’s insights enter by concurrence, as when we viewed the tragic mass of Michelangelo’s St. Peter’s, undercut and over-plastered with Bernini’s marble cupidons as big as hippos. It seems Frye was already a modern man, I still a modern repudiator. I hardly know how far his search joined with mine, from the struggle of Michelangelo’s Judgment and Ceiling, back in time through Angelico’s Quatrocento chapel, through Cavallini’s sterner mosaics and Judgment fresco (though I saw that alone), the deepening mystery of the Dark Ages, to the lower church of San Clemente and finally the Aurelii tombs, where Christianity brought Gregorian and Augustinian peace into the cave and ruin of Roman sick personality. Yet I am sure I wrote for the group, as we left that city of Mussolini and desolate palaces, heading for Assisi:

We were all glad to escape the noise and glory of Rome, and are in hopes of seeing tomorrow some really good art unmarred by Baroque alterations.

Although my cultural history would require later trips to photograph just that despised exuberance, it was good at the time to have art passions, and to find them discriminatory. So scorning Perugino’s Perugia and celebrating Piero della Francesca’s Arezzo, we came to the loved center of Florence – as in my Delta Return (1956): “the heart’s best home, / Nest of the migrant wings, the Tuscan town / And singing towers of the Western dawn.”

The four of us who have come together to Florence spent the whole morning in the Ufizzi. A joy to see it again. We only got to the first six rooms, but stood before the greatest pictures, Cimabue, Giotto, Simone, the Botticellis, over half an hour each . . . observing, sometimes discussing––though not as the guides discuss.

What prompted Norrie’s most irreverent outbreak was the old church of San Vitale in Ravenna, where the mosaics of Theodosius’ choir yield elsewhere to a lush abandon of Baroque. I recorded:

Frye says that when he gets to heaven his first request of St. Peter will be to let him rape a baroque angel.

It was in that brief Ravenna stay that I insisted on dragging everybody, on foot, through the April dust and sun, five miles out of town to the church of Santa Maria in Porto Fuori, to see some Giottoesque frescoes of the school of Rimini. They were of interest; but, as I wrote:

The walk back amounted almost to a dog-trot, as we were late for the train. The flat land under burning sun took me back to my Delta home. The hotter, the dustier, the more I revelled and put on speed, and the madder my oppressed friends became.

I still see Norrie’s platinum hair flouncing along, he wiping the sweat from his Canadian brow in a kind of ironic fury.

My art journals could follow him to Venice, but only to voice such opinions as he wrote better in his “Two Italian Sketches” (pub. 1942):

Veronese shows Venice as a huge blonde bawd getting rained on by a torrent of gold, and that would be all right to the Venetians.

Leaving art, what of the politics his sketches are so full of? We were all in agreement about Fascism, the Mussolini signs and slogans plastered everywhere: in Florence the highest praise of the guide bestowed on the death mask of Lorenzo il Magnifico, statesman and poet––“He looks like Mussolini.” I, who had written off civilization in cynical despair, could almost shrug with the Florentines I loved. But Norrie, most intelligent and moral humanist among us, was no doubt the most troubled. Not until the next Christmas would the Jewish persecutions in Cologne and up the Rhine, the complacence of good Germans and the Nazi zeal, sear its way into being the preoccupation of my journals, as of the novel they would later seed. How often there, in characters bearing other names, the voice is the voice of Frye.

That following year Norrie spent in Canada. I mostly pursued the bifurcation of Paolo-and-Francesca passion and of medieval art-faith, even to the Easter 1938 stay at Solesmes Abbey, absorbed in the peace of Gregorian chant and reciting religious poetry (from the thirteenth to the seventeenth centuries) to Simone Weil, whom I knew only as “the Girl of Solesmes,” she me as “the young Englishman” –– as with Frye, a puzzling resonance under a surface almost of anonymity.

Our last fall (1938) Norrie came back to Oxford as the rest of us returned from the crisis-harried continent.

[Here are journal entries from September 26 to October 1 with news of current events, including Chamberlain’s infamous speech after the Munich Agreement of September 29.]

It was not until a week later that I wrote:

Tonight I have been to Rodney’s digs. Mike Joseph and Norrie Frye, who live in the same house, came in, and we had a great reunion.

If only Norrie could have launched me, the year before, or now that he was back on the scene, into the orbit of the avant garde, which sooner or later I would have to come to terms with. No doubt he tried. He had urged all of us to Eliot’s Murder in the Cathedral when it hit Oxford. That Christmas of ’38 in Paris he had converted Rodney Baine to modern art. I note the big Phaidon book on The Impressionists given me at the time––surely for my soul’s health. But I clutched for the hand rail:

Norrie ranks Picasso with Michelangelo and Beethoven as one of the world’s great revolutionary artists. He has better taste than I. Where he sees power he can admire it. At my stage, prejudice precludes enjoyment.

It is only in these last years that I have pushed my Symbolic History toward participation in that cloven Now:

How can an entropic universe be other than a tragic universe, its glory reared on the leap of flame? Our task is to celebrate the dangerous radiance of the later West without the soul-abandon of [Robinson] Jeffers’s dance around the funeral pyre: Someone flamelike passed me saying, “I am Tamar Caldwell, I have my desire.”

Norrie’s greatest service to me that year (besides being himself) moved the other way: he played the Elizabethan music I was buying, Byrd and the rest, on the piano that was in my digs. He was a sensitive pianist, and it revived Spenglerian delight to hear him read through those loved variations on “The Woods So Wild.” In return I would put my medieval and early-Renaissance records on the gramophone––all those incomparable performances from the Anthologie Sonore, Lumen, and L’Oisseau Lyre, which I had bought in Paris that January and would go on buying and playing for everyone, as if they were the key to salvation itself.

By June, when my thesis on the Elizabethan poet Edward Fairfax was just proceeding, like Hamlet’s father with all its imperfections on it, to the examiners, those records and my spiel about their cultural correlations, brought various strangers to hear them. One was Somerset, historian of Worcester College, who got marvelously excited, assembled his students to sample Leonin, Perotin, Machaut, Landini, Dufay, and the rest, verbally enmeshed, as they already were, in my budding Symbolic History. He offered to get me a fellowship if I would stay on with those treasures and pursue my work; but I had contracted for U.S. return, marriage, a job. It was not until last year, reading in Lyndall Gordon’s book, Eliot’s Early Years [1977], how one of the god-fathers at the 1926 baptism was “Vere Somerset . . . fellow of Worcester,” that I sensed the magnitude of what I had refused (“il gran rifuto” [Inferno 3.60]).

My records also lured Hough (Gough?), choir fellow of Lincoln College. The last Frye entry in my Journals records also the last I saw or have heard of Hough:

June 16, 1939. When I had got the thesis in, I wandered about dazed for a time, then scurried to the library to copy music. For tea Mil [Mildred Winfree] and I were invited to Hough’s. We caught Norrie Frye by chance and took him along. Hough has a pretty virginals, a viola da Gamba as old as Bill Shakespeare and with as sweet a tone, also numerous recorders. He plays them all skillfully and sings with taste. Norrie had never played the virginals, but softness of touch (not even the piano can tempt him to pound) and love of that music made him immediately proficient.He and Hough gave us two Handel sonatas, the first for viol and virginals, the second for treble recorder and virginals. We all tried Gibbon’s madrigal “The Silver Swan,” Mildred singing soprano, Hough the alto, I sounding the third part on the treble recorder, Hough again the fourth on the viol, while Norrie gave us the bass and reduction on the virginals. After tea one of Hough’s choir boys came in, and he and Hough did the best thing of the afternoon, a thirteenth-century three-part motet, very winsome and coy, “Ut Celesti” (still unrecorded). Hough sang the first part and played the third on the viol, while the boy sang half of it in falsetto and finished on the recorder.

If only my experience of these thing[s] had begun before.

I went to drab teaching in the plains of Illinois and Iowa, while the bombing of Europe destroyed so much of what we had loved. When I returned abroad in 1948 on a Rockefeller grant, the slowly submerging past seemed a quaint and sheltered land––flamboyant stone, sonnets, democracy, and madrigals: the future an expanding universe of vacant and alarming dimension, in which rockets and moon-flight beckoned, where a towering cloud of atoms billowed eternal fear.

Visiting with Professor [Ernst Robert] Curtius on the Via Flaminia just outside Rome, I was one of twelve at dinner: German books on the shelves, German philosophy in the German tongue. We drank, however, Alban wine. I set it down:

Expatriots [sic], a Russian countess, German intellectuals fled from Hitler, one Yugoslav of the latest harvest. Two bearded Swiss professors beamed like patriarchs not yet surrendered to the flood. The daughter of one played Beethoven on the grand piano Fischer had played when last in Rome. I heard the wolves of Naples at the door. When I spoke of the time and of these apprehensions, Curtius fell into gloom. “What you say has truth,” he said, “but it is sad.” We sipped our wine.

In the shadow of the vaulted room, visions descend upon me . . .

In the last drench of sun giant towers drown. Only the new ships riding into the wind, a proud white crest of foam at the bows. This little vigil of life, do not deny, hurled over the watery round, flame of the ultimate West.

[Curtius died in Rome in 1956.]

Suppose the imprint of Northrop Frye had brought his platinum-haired presence into the room? It would surely have testified to what he had known and I had painfully to grope to: That as long as civilization is here, it is on-going; that what it requires of us is not only poetic immersion in its tragic mystery, but the antimony he had practiced from the start: the clear and constructive warfare of critical intelligence.