Yves Saint‑Cyr has recently completed a Ph.D. dissertation entitled The Glass Bead Game: From Post‑Tonal to Post‑Modern (University of Toronto). It’s an intellectually ambitious and stimulating romp through a wide range of complex literary, critical, and musical texts, painting, and mathematical theory. In his chapter 3 Saint‑Cyr turns to Frye in order to illuminate Hermann Hesse: Frye’s theory of modes and his theory of the phases of the mythoi of comedy can, Saint‑Cyr argues, help reveal the formal structure of Hesse’s Das Glasperlenspiel. But as Saint‑Cyr says early on, the ends and means of this project can be reversed: he wants to investigate the implications of Hesse’s Glass Bead Game “to model the role of recursive paradox in literary criticism.” This seems to point in the direction of Frye as a Glass Bead Game player. Saint‑Cyr does say that Frye might well conceive of literary criticism rooted in mythology as a Glass Bead Game, an inference he makes from one of the three places in his writing where Frye refers to the Glass Bead Game, but he never really develops the idea that Frye’s critical constructs are themselves a Glass Bead Game.

Not that he should have, but there is certainly enough in Frye’s published works to make such a case. Bloggers interested in the topic should consult Graham Forst’s “‘Frye Spiel’: Northrop Frye and Homo Ludens,” Mosaic: A Journal for the Interdisciplinary Study of Literature 36, no. 3 (September 2003): 73–86. Forst argues that “play is reading’s central motif and that for Frye, readers see things holistically only when “playfully” detached: literature “is the quintessential ‘playful’ medium because it is ‘detached from immediate action.’” But I suspect the last word on Frye and homo ludens [“man at play”] will have to take account of what he both says and implies about play in the notebooks, considering such constructs as the Great Doodle, the ogdoad (which began when Frye was nine as a dream of writing eight concerti), and the omnipresent HEAP (Hermes‑Eros‑Adonis‑Prometheus) scheme. These are all like a giant board game, a centripetal structure on which Frye continually moves the pieces as he works to show how imaginative patterns inform self and society, cultural creations, history and philosophy––indeed, everything in the poetic and religious cosmos.

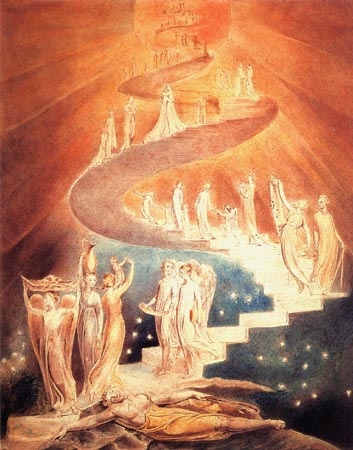

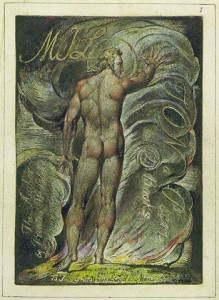

The notebooks reveal the expansive free‑play of Frye as himself as homo ludens. His own comments on his expansive “game” illustrate that in the tradition of both Huizinga and Schiller (and of the anatomy form itself) playing the game is serious business. The game has scores of lesser doodles––permutations, based on schema that Frye has drawn from alchemy, the zodiac, the chessboard, musical keys, colors, the omnipresent “four kernels” (commandment, aphorism, oracle, and epiphany), the shape of the human body, Blake’s Zoas, Jung’s personality types, Bacon’s idols, the boxing of the compass by Plato and the Romantic poets, the Greater Arcana of the Tarot cards, the seven days of Creation, the three stages of religious awareness, numerology, among other schema. Then there’s Frye’s enigmatic “chess‑in‑bardo,” which involves a dialectic of two opposing forces: agon and anagnorisis, choice and chance, descent and ascent. All of these things can be seen as a web or net of interconnected imaginative processes, like the jeweled net of Indra. To use Saint‑Cyr’s phrases, it’s a “conceptual model” and an “epitome of symbolic construction.” The game involves the organizing of cultural symbols, literary ideas, poetic motifs, philosophical categories on a two‑dimensional grid, like a game board. Its form is both dialectical and cyclical and at times, when Frye speaks of the gyre or vortext, it’s even three‑dimensional. It’s not unlike the description of the Glass Bead Game that Hesse’s Knecht provides in his letter to Tergularius, where “every symbol and combination of symbols led . . . into the center, the mystery and innermost heart of the world, into primal knowledge” (Magister Ludi, 104–5). This sounds like a description of Frye’s own ogdoad.

Continue reading →