Frye says of Robert Burton that his “tremendous erudition never blunted the edge of his sense of humor” (“The Times of the Signs”), and we might say the same about Frye. Here are a few of the hundreds of passages in which Frye writes of humor:

For many readers of Paradise Lost the contrast between the domestic, highly cultivated atmosphere of Eden and the nudity of the inhabitants seems grotesque, like Manet’s picture Déjeuner sur l’herbe. But Milton’s approach to his subject is thoroughly consistent with his view of the human state, and it is by no means humorless: in fact a careful reader of Paradise Lost can easily see that one of the most important things Adam loses in his fall is his sense of humor. Humor, innocence, and nakedness go together, as do solemnity, aggressiveness, and fig leaves. (Northrop Frye on Literature and Society, 86)

A sense of humor, like a sense of beauty, is a part of reality, and belongs to the cosmetic cosmos: its context is neither subjective nor objective, because it’s communicable. (Late Notebooks, 1:227)

All literature is literally ironic, which is why humor is so close to the hypothetical. If you don’t mean what you say, you’re either joking or poetizing. (Northrop Frye’s Notebooks for “Anatomy of Criticism,” 264)

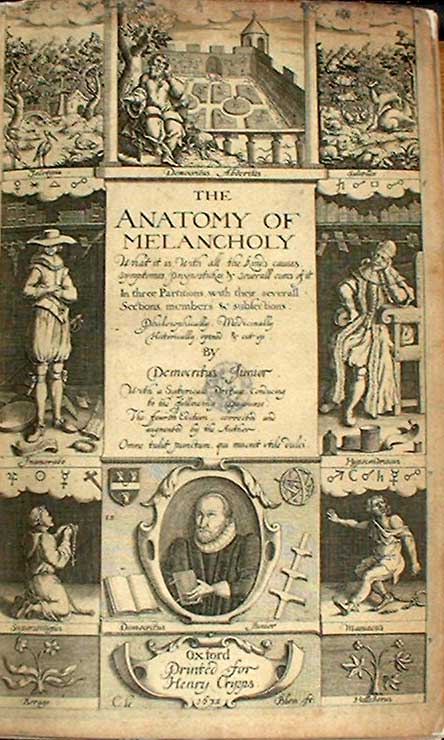

In Synge’s Riders to the Sea a mother, after losing her husband and five sons at sea, finally loses her last son, and the result is a very beautiful and moving play. But if it had been a full-length tragedy plodding glumly through the seven drownings one after another, the audience would have been helpless with unsympathetic laughter long before it was over. The principle of repetition as the basis of humor both in Jonson’s sense and in ours is well known to the creators of comic strips, in which a character is established as a parasite, a glutton (often confined to one dish), or a shrew, and who begins to be funny after the point has been made every day for several months. Continuous comic radio programs, too, are much more amusing to habitués than to neophytes. The girth of Falstaff and the hallucinations of Quixote are based on much the same comic laws. Mr. E.M. Forster speaks with disdain of Dickens’s Mrs. Micawber, who never says anything except that she will never desert Mr. Micawber: a strong contrast is marked here between the refined writer too finicky for popular formulas, and the major one who exploits them ruthlessly. (Anatomy of Criticism, 168-9)

Two things, then, are essential to satire; one is wit or humor founded on fantasy or a sense of the grotesque or absurd, the other is an object of attack. Attack without humor, or pure denunciation, forms one of the boundaries of satire. It is a very hazy boundary, because invective is one of the most readable forms of literary art, just as panegyric is one of the dullest. It is an established datum of literature that we like hearing people cursed and are bored with hearing them praised, and almost any denunciation, if vigorous enough, is followed by a reader with the kind of pleasure that soon breaks into a smile. (ibid., 224)

Humor, like attack, is founded on convention. The world of humor is a rigidly stylized world in which generous Scotchmen, obedient wives, beloved mothers-in-law, and professors with presence of mind are not permitted to exist. All humor demands agreement that certain things, such as a picture of a wife beating her husband in a comic strip, are conventionally funny. To introduce a comic strip in which a husband beats his wife would distress the reader, because it would mean learning a new convention. The humor of pure fantasy, the other boundary of satire, belongs to romance, though it is uneasy there, as humor perceives the incongruous, and the conventions of romance are idealized. Most fantasy is pulled back into satire by a powerful undertow often called allegory, which may be described as the implicit reference to experience in the perception of the incongruous. The White Knight in Alice who felt that one should be provided for everything, and therefore put anklets around his horse’s feet to guard against the bites of sharks [Through the Looking Glass, chap. 8], may pass as pure fantasy. But when he goes on to sing an elaborate parody of Wordsworth [ibid.] we begin to sniff the acrid, pungent smell of satire, and when we take a second look at the White Knight we recognize a character type closely related both to Quixote and to the pedant of comedy. (ibid., 225)

Yes, I think you are right in ascribing the failure of so many earnest men to a lack of humor. Humor arises from the perception of incongruities and discrepancies in human nature. The reformer is impatient of these discrepancies; he calls them the result of cynicism and skepticism. His outlook is too exclusive and narrow for them, because he wants to apply a few formulas to the world which, universally accepted, would cure all of that world’s evils. Now a man who has a panacea in any sphere is a quack. And a quack is always a nuisance, generally a menace. Whether he makes himself ridiculous or not depends on the amount of humor possessed by his portrayer or auditor, not on his own. (This is the sample of the workings of a mind with mould clinging to it, as aforesaid). (Frye to Helen Kemp, on his 20th birthday, 15 July 1922)