Here is Clayton Chrusch’s detailed summary of Chapter Five of Fearful Symmetry:

The greater the work of art, the more completely it reveals the gigantic myth which is the vision of this world as God sees it, the outlines of that vision being creation, fall, redemption and apocalypse.

1. The Bible as archetype of Western culture

For a Christian, the totality of creative power is called the Word of God or Jesus. This creative power sees a vision of all time and space whose mythic shape is the same as that of the Bible: “creation, fall, redemption and apocalypse.” Frye writes, “all works of art are phases of that archetypal vision,” and the greatest art, such as the Bible, most completely reveals this vision.

Blake viewed the central myth of the Bible as a genuine vision of reality, and his work as aligned with it. This Biblical vision is an imaginative one, however, and Blake dismissed as irrelevant questions of historical veracity. Blake also rejected what he considered stupidly orthodox readings of the Bible of the kind that attempted moral justification of God’s Old Testament bloodthirstiness. Rather he saw such passages as true visions of a false god, and he saw such perverse orthodoxy as Anti-Christ. The Bible, though, is not a unique or exhaustive expression of the Word of God, rather all nations, in Blake’s view, had the same genuineness of vision, though the ancient Greeks in particular obscured and forgot theirs.

In art, the most complete vision is cyclic, and in poetry this complete form is called epic and properly covers “the entire imaginative field from creation to the Last Judgement” though, like the Bible, it is most concerned with the the world’s cyclical movement between the opposite states of falleness and redemption. Non-epic forms can be considered as particular episodes within the universal epic vision. As such, literature, at least Western literature, can be seen as more conventional than is commonly acknowledged.

2. The poet’s meaning is often different from what he thought he meant.

Blake sees creative actions as an artist’s real life. Actions and thoughts “on the ordinary Generation plane” may have nothing to do with an artist’s creativity. This is why Wordsworth’s preface to the Lyrical Ballads is “twaddle,” while the poems themselves are clear visions, and why in general we cannot trust or limit the meaning of art to the artist’s conscious intention. The real intentions that produce art are often sub- or super-conscious.

3. “Reality is intelligibility, and a poet who has put things into words has lifted ‘things’ from the barren chaos of nature into the created order of thought.”

Blake held diction to be very important though he makes few statements about it. His position begins, as it usually does, with a rejection of Locke, in particular, he rejected the notion that words are inadequate substitutes for real things. On the contrary, words make things intelligible and therefore more real. The meaning of a word, beyond generalities, is undefinable because it depends both on its context and its relation to human minds. The sounds, rhythms, and associations of a word–attributes that have little to do with its general definition–are functional in poetry and can give a word a meaning that is beyond the capacity of any dictionary to capture.

As for rhyme and meter, Blake insists that “the sound, sense and subject are to make a complete correspondence at all times” which means that fixed stanzaic patterns may be appropriate for short lyrics but rhyme is dropped in the longer works and meter and line length are varied according to the content.

4. Right and wrong kinds of allegory

We should understand poetry by unified and immediate perception. We might have to do hard intellectual work in order to unify the poem in our minds, but it is the direct experience that is the meaning of the poem. The intellectual scaffolding that helped us achieve that experience should just fall away. “For,” as Blake writes, “[a poem’s] Reality is its imaginative Form.” The wrong kind of allegory is “merely a set of moral doctrines or historical facts, ornamented to make them easier for simple minds.” The wrong way to read allegorical literature is to reduce it to such a set of abstractions. Great allegorical writing exists, and it is great not because of the quality of ideas it represents but because of the imaginative power of its vision.

5. The power of religion lies in its poetry.

We cannot hold to art as good or true because art envisions both good and bad, true and false. Religion does claim sure and reliable knowledge of truth and goodness, but there is something false about this claim. The power of religion lies not in dogma but in the visionary masterpieces that the dogma is derived from. The poet’s task is to go back to the symbols of those masterpieces and to recreate them. The meaning of these symbols (for example, the gods of ancient Greece) becomes more vague over time and the artist’s function is to clarify it.

This is what Blake does. One of his tactics is to use unfamiliar names for his characters. Though he could have called his sky father Zeus, Blake called him Urizen to head off the vagueness that comes with Zeus’s large cloud of associations.

Christianity is not more true than other religions, but its imaginative core, what Frye calls, “its vision of the humanity of God and the divinity of risen Man” is that characteristic imaginative accomplishment of Christianity that “all Christian artists have attempted to recreate.” Even secular writers like Shakespeare and Chaucer are informed by “the universal Word of God, the archetypal vision of ‘All that Exists.'” This vision provides the most profound kind of signficance to all worthwhile art and makes such art allegorical in the sense Dante used when he spoke of anagogy.

6. In art, all creatures are human.

Frye writes, “It is the function of art to illuminate the human form of nature.” By this he means that art “interprets nature in human terms.” Only a human being can create a design, but that does not stop art from seeing design in the pattern of a snowflake. Blake’s tiger has a human creator that makes the tiger’s form, which is therefore a human form.

7. An Outline of Blake’s central myth.

Part six of this chapter concludes with what is already a very good summary of Blake’s central myth:

Its boundaries, once more, are creation, fall, redemption and apocalypse, and it embraces the four imaginative levels of existence, Eden, Beulah, Generation and Ulro. It revolves around the four antitheses that we have been tracing in the first four chapters, of imagination and memory in thought, innocence and experience in religion, liberty and tyranny in society, outline and imitation in art. These four antitheses are all aspects of one, the antithesis of life and death, and Blake assumes that we have this unity in our heads.

It is difficult to summarize Frye’s summary of Blake’s mythology, since Frye has already reduced it to essentials. I refer readers to Frye’s summary but I nevertheless attempt the following summary squared.

Blake’s central myth draws from a number of sources, in particular Greek mythology, the Bible,and the Icelandic Eddas.

Imaginatively, all human beings are part of larger human beings, and ultimately part of one being who, for Christians, is Jesus. The intermediate beings are called Eternals and are imaginatively related to giants and Titans. One of these Eternals, and a central figure in Blake’s cosmology, is Albion who includes everyone in our world as seen from Blake’s English perspective.

History is divided into seven fallen ages which Blake calls the “Seven Eyes of God.” It is preceded by an unfallen Golden Age and followed by an apocalypse which Blake sometimes calls the “Eighth Eye.”

The Fall ends the Golden Age, and occurs in Beulah when Albion falls into mental passivity by conceiving of the object-world as independent of him. He thus falls into Generation, and the objective world becomes Mother Nature or the “female will”. Each of the seven eyes begins with an attempt by “the yet unfallen part of God” to awaken the sleeping Albion.

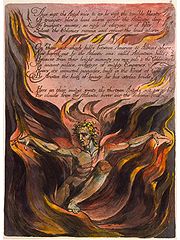

The Fall continues to unfold through the first three eyes, called the silver, bronze, and iron ages or Lucifer, Moloch, and the Elohim. The silver age is characterized by great powerful warring gods and Titans and the threat of utter chaos which is finally put down by a sky-god figure which Blake calls Urizen and who represents “moral law and tyrannical power.” Order is established at the cost of a weakened imagination and a suppression of revolutionary energy, personified by Blake as a Prometheus figure called Orc.

The bronze period is the beginning of a period of what Blake calls Druidism, the worshipping of death through endless war and massive human sacrifice. The period of Druidism continues not only through the bronze period, but through the following three as well.

The period in which things achieve their current shape is called the iron age or Elohim period. Human beings, in our full power are giants, and as we lose power we contract, and this contracting would annihilate us if it were not for an act of mercy that occurs at this point in the myth: the unfallen part of God creates human bodies as we know them now (the “Limit of Contraction”). He also creates the universe as we see it (the “Mundane Shell”). For Blake, this is the significance of the story of Adam and Eve.

As Frye writes, “the remaining four eras or Eyes of God are divided into twenty-eight phases or ‘Churches’ and “The first twenty of these Churches cover the remainder of the Druid period and the fourth and fifth eyes of God, Shaddai and Pachad.” These phases represent dominant civilizations that survive in the Old Testament as geneologies. The fourth eye ends with Noah and the flood. The fifth ends with the decline of human sacrifice and the period of Druidism symbolized by Abraham substituting an animal for Isaac in his sacrifice. The sixth age, or age of Jehovah, consists of the remaining Old Testament period from Abraham on, and the seventh begins with the birth of Jesus. The Churches of the Jesus period are Church Paul, Church Constantine, Church Luther which all consolidate tyranny and which degenerated into into Deism, followed by Church Milton which initiates an apocalypse that begins in earnest with the French and American revolutions.

8. The sinister symbols: Satan, Serpent, Dragon, Covering Cherub, Tree of Mystery, Great Whore

In this section Frye tackles Blake’s dense web of demonic and lower-worldly symbolism.

In the seventh age, the apocalypse begins with a return of the revolutionary energy of Orc, but opposed to this energy is a materialist tyranny represented by Satan. Frye describes Satan as the death impulse, the Selfhood, the accuser, the principle of unbelief. He is associated with rock and sand because they are not alive. But Satan too is a merciful creation in the sense that there is something worse than death, namely chaos, and non-entity is worst of all. Therefore Satan is called the “Limit of Opacity.”

Blake includes in this cluster of demonic images the serpent of the garden of Eden as well as the tree of the knowledge of good and evil which Blake calls the tree of mystery. The serpent, actually, takes a number of symbolic forms: a Satanic form that tempts Adam, an Adamic form representing fallen humanity, and a Messianic or revolutionary form, where it is nailed to the tree of mystery as Orc, representing death and rebirth. The serpent also has a Chaotic form which is more sinister than its Satanic form. In this form, it manifests as a dragon ridden by Rahab or the Great Whore (Mystery), a Covering Cherub blocking the way to Eden, or as Leviathan. This symbolism means that the basis of all tyranny is chaos.

The unfallen world is regained when the Whore and the dragon representing “all the evils of the Selfhood” are thrown into the fire and go from chaos to nonexistence.

The zodiac is a sinister symbol associated with Druidism and representing “indefinite or endless recurrence.”

Arthur is another important Blakean symbol associated confusingly with all three of Albion, Satan, and Leviathan.

9. Blake’s anatomy of poetry

Blake’s characters are vivid creations but remarkably simple. Orc, for instance, is simply a hero. He represents heroism which is not a concept or a fact but an essential imaginative form. The intellectual powers understand imaginative forms, but the corporeal understanding demands that every symbol map to a fact or concept. Blake’s poetry is difficult because it only addresses itself to the intellectual powers. The value of this method is proved by its application to the Bible which is repulsive nonsense when interpreted by the corporeal understanding, but a vision of creation, redemption, and revelation when interepreted by the intellectual powers. The same can be said of Blake’s own poetry.