Today is Da Vinci’s birthday (1452 –1519)

Monthly Archives: April 2010

Alvin Lee: “What The Great Code Is and Does”

Cross-posted in the journal’s Frye archive here.

The Great Code is a powerfully structured and intricately detailed prose poem about the possibility of human love and freedom through a new kind of understanding of the Bible. By a process of imaginative literalism, the author invites the reader to confront the major challenges of the Bible–its sheer length, its complexity, most of its 80 books, its having been composed during more than a millenium, its being read in translation by most readers, its unifying but also its fragmenting characteristics, its traditional claim as the Word of God told through human agents, all this and more–in the hope that the old writings will breathe new life and so enable genuine individuals to be born, imaginatively and spiritually. The intention is to free the hoary ancestral text from centuries of doctrinal accretions and of having been misread as history when it is not, except in vestigial ways, so that it can work again for thinking men and women (not necessarily religious ones) as the great visionary document of Western culture.

Throughout his life Frye became increasingly aware of the enormous shaping influence of the Bible, not only on individual poets and writers but also, more generally, as what he called the mythological framework of the culture. He came to see as well that the Bible was in danger of becoming extinct for most educated people, as growing numbers moved away from religious traditions, and as other cultures clamoured for attention. He became convinced that the assumption of “a contrast or opposition between the religious and the secular, the sacred and the profane, does not work any more, if it ever did. Everything in religion,” he says, “has its secular aspect, and everything in secular life has religious implications, however ignored or undefined they may be.”[1] After long pondering, then, he set about defining some of these implications and accepted the pressures, external and internal, actually to write what was already being talked of as his “big book on the Bible.” He recognized as he did so that he was not in any conventional sense a Biblical scholar. The Great Code is presented as his “own personal encounter with the Bible” (Introduction, 1). It is also the response to the Biblical text, I add, of one of the twentieth century’s most erudite and creative minds and imaginations. Long ago, Carlos Baker, reviewing the manuscript of Fearful Symmetry for Princeton University Press, had written: “he knows the Bible as few scholars do” (Ayre, 192). Baker’s comment points to at least two things: Frye’s thorough reading knowledge of the Bible and his extraordinary way of knowing it. In his Blake book Frye had said, “Even the Bible must be shaken upside-down before it will yield all its secrets” (FS, 120).

Frye’s immersion in the Bible began early in his life and his insights into it expanded steadily, both before The Great Code appeared (1982) and in the following eight years, culminating in his last big book, Words with Power, Being a Second Study of the Bible and Literature (1990). In the next half hour, I try to provide you with a synoptic account of how Frye saw the Bible and how he hoped readers would approach it. I shall concentrate on the shape and meaning of only the first half of The Great Code. If you have questions or comments about the rest or about the later book, Words with Power, we can talk about those in a few minutes.

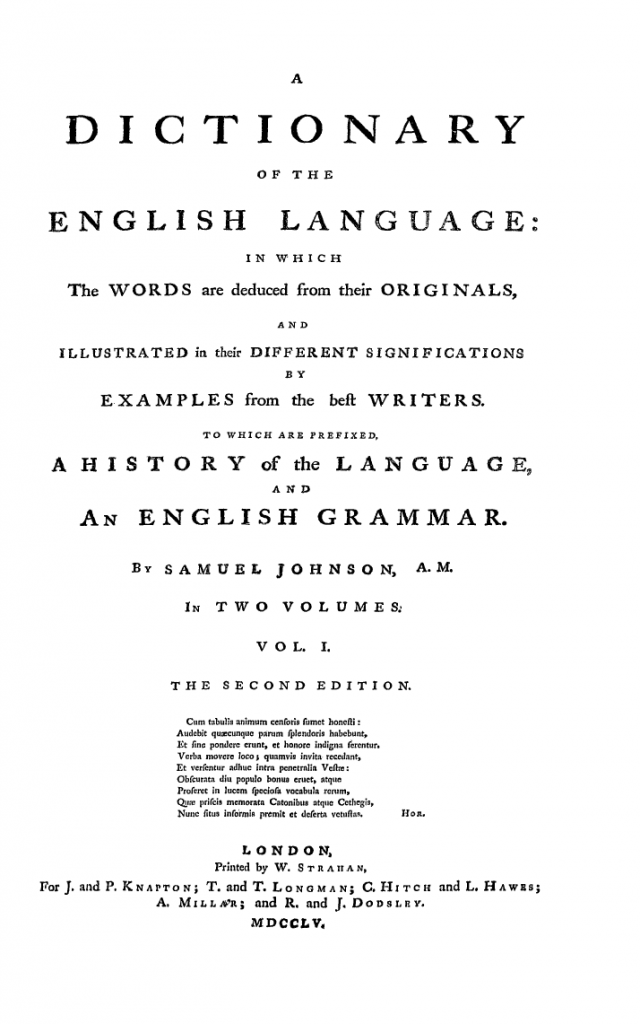

Samuel Johnson’s Dictionary

On this date in 1755 Samuel Johnson’s A Dictionary of the English Language was published.

Frye in Anatomy on Johnson’s “bumbling” but still “colloquial and conversational” style:

Students in English are often urged, in Romantic fashion, to use as many short words of native origin as possible, on the ground that they make one’s vocabulary concrete, but a style founded on simple native words can be the most artificial of all styles. Samuel Johnson at his most bumbling is still colloquial and conversational compared to a William Morris romance. Standard educated English speech today, with its many long abstract and technical words and the heavy accent on its short ones, is a polysyllabic clatter which is much easier to fit to prose than to verse. (AC 270)

Expanded Front Page

Handel’s Messiah

httpv://www.youtube.com/watch?v=u6_nJ11BgTE

London Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Sir Colin Davis, Halelujah Chorus

On this date in 1742 Handel’s Messiah premiered in Dublin.

Frye on Handel in his remarkable student essay on Romanticism:

The rhythm force of music is incarnated and symbolized in the dance. Hence, men like Bach, Handel, Mozart were all dance composers. The suite or selection of dances in one key was a standard artform, and later, when the sonata sublimated the dance rhythm of the suite into a stricter form, the minuet, in many ways the typical dance, was often retrained. (CW 3, 54)

Jacques Lacan

httpv://www.youtube.com/watch?v=URsYj-TVFjc

Lacan on the unconscious (French with English subtitles)

On this date Jacques Lacan was born (1901 – 1981).

A telling citation of Lacan in Notebook 52:

The Jewish Sabbath begins at sundown on Friday, which is Venus’ day: white goddess modulating into black bride. I’m sure the Tempest masque and the exclusion of Venus from it are connected, what with the insistence on preserving Miranda’s virginity. Lacan is wrong: it isn’t just the phallus that’s lost, but since the Fall every sexual union has had, or been, a screw loose. Yeats’s poem on Solomon and Sheba is the one to consult. (CW 6, 454)

Samuel Beckett

httpv://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NdTjRumkT9k

Beckett’s Play, Part 1 (Part 2 after the jump)

On this date Samuel Beckett was born (1906 -1989).

Frye in “City at the End of Things” in The Modern Century says this about Beckett’s Waiting for Godot

There are two contemporary plays which seem to sum up with peculiar vividness and forcefulness the malaise that I have described as the alienation of progress. One is Becket”s Waiting for Godot [the other is Albee’s Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?]. The main theme of this play is the paralysis of activity that is brought about by the dislocation of life in time, where there is no present, only a faint memory of the past, and an expectation of a future with no power to move towards it. Of the two characters whose dialogue forms most of the play, one calls himself Adam; at another time they identify themselves as Cain and Abel; at other times, vaguely and helplessly, themselves crucified, with Christ. “Have we no rights?” one asks. “We got rid of them” the other says — distinctly, according to the stage direction. And even more explicitly: “at this place, at this moment of time, all mankind is us.” They spend the whole action of the play waiting for a certain Godot to arrive: he never comes, they deny that they are “tied” to him, but they have no will to break away. All that turns up is a Satanic figure called Pozzo, with a clown tied to him in a parody of their own state. On his second appearance, Pozzo is bind, a condition which detaches him even further from time, for, he says, “the blind have no notion of time” (CW 11, 25-26).

Frye Alert

Here are some papers on Frye posted as PDFs on the web.

Dr. Marek Oziewicz, “Myth and Archetypal Criticism”

J. Thulasi, “‘Imagination at the School of Seasons’ — The Educated Imagination — An Overview”

Edward Jayne, Review of The Critical Path

Wynton Kelly

httpv://www.youtube.com/watch?v=P4TbrgIdm0E

On this date in 1971 jazz pianist Wynton Kelly died at age 39 of a seizure.

Here he is with Miles Davis and John Coltrane performing “So What”.

Nella Cotrupi: “Process and Possibility: Northrop Frye’s Spiritual Vision”

Nella Cotrupi‘s talk to the Frye Festival in 2002. It is cross-posted in the journal’s Frye Archive here.

Mesdames et messieurs, ladies and gentlemen, it was with real pleasure that I accepted M. Lemond’s invitation to speak to you today about a man whose visionary faith and potent words profoundly touched and changed my life, as he has the lives of so many others. Northrop Frye’s reputation continues to rest primarily on his prodigious output in the realm of literary criticism and theory. Today, however, I want to invite you to explore with me the driving force that fuelled his work as a literary critic and teacher, and that has made his ideas so compelling, not just for those on the literary and critical path, but for thinking and socially-concerned people around the globe. My talk will focus on Frye’s spiritual quest, on his unique, unconventional version of Christianity, and on some of the spiritual and philosophical traditions from which he drew inspiration and, dare I say it, hope.

But first, I want to tell you a story. Appropriate, I think, considering the occasion. This is a real life story about a committed young lawyer and activist who decided in the early years of her marriage to take some time away from her professional activities to look after her young children. Those days in the early 1980s were exciting and heady ones for a newly minted lawyer whose work revolved around law reform and advocacy for injured workers in Ontario. Granted, many of these workers were men and women with whom she felt a deep affinity, being, like her parents, immigrants, workers of Italian origin employed in manufacturing, and construction—working long hours in often dangerous conditions and unsavoury surroundings.

They were people determined to move forward, often at great cost, physical and otherwise, to themselves, in order to bring other options and possibilities to their children. And there were other clients too—all with similar dreams and aspirations—workers from the Caribbean, Portugal, and South America, Europeans and Asians from many lands and even a few Canadians whose history freed them from the need for hyphenation. All of them were hungry for the opportunities promised by this immense northern land, and all of them shattered by the possibility that the hard-won morsel of hope for a better life might suddenly be snatched from them by the physical and other injuries they had sustained.

To leave this work and vocation, even for a temporary sabbatical, was a difficult call to make. And yet, the value system was deeply ingrained and the family priorities won out. A leave was arranged, an application sent out for a part-time MA to keep the brain from getting too flaccid with diaper changes and baby talk and well, you can probably guess the rest. She walked into room 114 Northrop Frye Hall at Victoria College to sit in on Frye’s Bible lectures and she has never really walked out. Suddenly those persistent, suppressed, impractical preoccupations which had haunted her since childhood were given legitimacy and a most articulate voice. So too were those emotions that had driven her as a child to try to capture in words, or with paint and brush the quiet majesty of the Laurentians, the heart-aching sunsets over northern Ontario lakes with their frame of wind-tossed pines, the hard cold beauty of star-filled winter skies over Nipissing, and even, on occasion, the harsh beauty of Calabria’s mountains. She was free to confront these compulsions now and to ask: Why had she felt moved by these vistas to the innermost core of her being, why compelled to capture and hold the intensity of the moment and what, just what, was one to do with such powerful experiences?