The University of Toronto has many claims to fame. It has a stellar academic reputation, one of the best libraries in the country, some of Canada’s finest faculty, and Maclean’s consistently ranks it as one of the best universities, if not the best, in the country. That being said, the University of Toronto has adopted dubious practices when it comes to advancement and academic freedom.

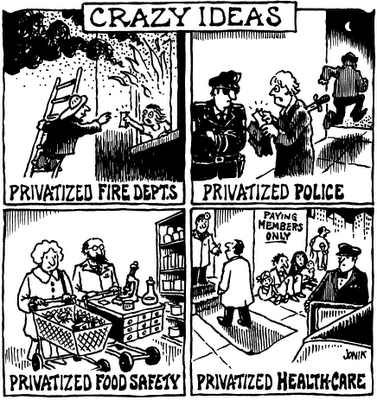

What are the questions that a university must ask itself when it receives donations? Among them are, What is the purpose of the donation? What are the conditions attached to the donation? How important is academic freedom to the success of the University’s researchers, professors, and students in relation to the donation?

The University of Toronto’s Vice-President of Advancement, David Palmer, claims that all donor agreements are subject to the following clause:

The parties affirm their mutual commitment to the University’s Statement of Institutional Purpose which includes a commitment to foster an academic community in which the learning and scholarship of every member may flourish, with vigilant protection for the rights of freedom of speech, academic freedom and freedom of research.

In two recent donations to the University of Toronto, this clause never appeared, nor did any that remotely resembles such a clause. Moreover, when I Google-searched this clause, I realised that it appears nowhere except in a letter to the editor of the Toronto Star on September 19, 2010, written by the Vice-President of Advancement, and subsequently published in the Varsity, a student run newspaper at the University of Toronto. The reason for the letter in the Star is that an excerpt from The Trouble With Billionaires by Linda McQuaig and Neil Brooks claims that the recent $35 million dollar agreement between Peter Munk and the University of Toronto “stipulates that the school will also house the Canadian International Council — a right-leaning think-tank that has been pushing to replace Canada’s earlier role as a leading UN peacekeeping nation with a more prominent role in U.S.-led war efforts.” The University of Toronto, through its Vice-President of Advancement, has assured us that this is not the case and that no donor has influence over the academic freedom of researchers, students, or professors at the University of Toronto.

In his chapter “Academic Freedom or Commercial License?” (which appeared in The Corporate Campus, edited by James Turk), William Graham highlights a few agreements between the University of Toronto and its donors. When, for exammple, Joseph Rotman donated $15 million to the University of Toronto, the agreement required “the unqualified support for and commitment to the principles and values underlying the vision by the members of the faculty of management as well as the central administration upon the continuing ongoing support demonstrated by members of the faculty” (23). In other words, for the donation to continue, Rotman required that faculty adhere to “the vision.” Indeed, as Graham notes, the acting provost at the time “stated with pride” that “given the magnitude and importance of the gift, the University is prepared to make a number of undertakings that in a number of ways involve new commitments or variances from previously approved allocations or from University policy” (24).

Rotman’s donation is not unique. Graham writes: “Even more scandalous in many ways was the agreement between the University of Toronto and Mr. Peter Munk, together with his corporations, Horsham and Barrick Gold” (24). In this agreement, the university will establish a “business-academic relationship,” and that “In return, the University promised Munk’s project would ‘rank with the University’s highest priorities for the allocation of its other funding, including its own internal resources.’ No mention wass made of the need to protect academic freedom or any other basic University policy” (24).

Graham is right to note that “Since Munk, like Rotman, could withdraw funding at any time over the 10 years if dissatisfied with the progress of the Centre, he was in a position to exert enormous influence over the teaching and research activities of the Centre. What, for example, might happen to an untenured faculty member of the Centre who spoke out in ways perceived as contrary to the interests of Horsham or Barrick Gold Corporations?”

The question that Graham asks is, of course, an important one. What happens when benefactors who donate money to a university disagrees with an untenured faculty member? What happens when benefactors can pull their donations to the University when they are not satisfied with the direction or “vision” of the program? In many regards, we already have answers to some of these questions. Virginia Ashby Sharpe in “Oversight, Disclosure, and Integrity in Science” writes:

We have also seen cases of institutional retaliation against researchers who have gone up against pharmaceutical manufacturers when their research indicated harmful effects. One case involves the University of Toronto. When Nancy Oliveri broke her confidentiality agreement and published unfavorable results regarding the drug deferiprone (used to treat the hereditary blood disease thalassemia), the university attempted to dismiss her. The same institution, which received a $1.5-million gift from the Eli Lilly company, rescinded its job offer to David Healy when he was publicly critical of the Eli Lilly drug Prozac.

All of this raises a further question: Would the University ever consider disbanding or disestablishing an entire program if the values and instruction of that program ran counter to the values or expectations of a benefactor? These seem to be important questions that need to be asked these days, especially in light of an Academic Plan which calls for the closure of several language programs to form a “School of Languages and Literatures” (now in search of a benefactor) and the complete destruction of other programs, such as Comparative Literature, Diaspora and Transnational Studies, and, of course, the Centre for Ethics.

Frye in his “Commencement Address at Carlton University,” delivered on May 17th, 1957, observes:

As John Stuart Mill proved a century ago, the basis of all freedom is academic freedom of thought and discussion. You have had that here, because you are responsible for carrying it into society. I know the staff of Carlton fairly well, and I know that none of them would try to adjust you or integrate you with your society. They have done all they could do to detach you from it, to wean you from the maternal bosom of Good Housekeeping and the Reader’s Digest, the pneumatic bliss of the North American way of life. They have tried to teach you to compare your society’s ideas with Plato’s, its language with Shakespeare’s, its calculations with Newton’s, its love with the love of the saints. Being dissatisfied with society is the price we pay for being free men and women.

That price we pay, of course, is something we choose for ourselves as scholars. It is not something to be negotiated because scholars are not to be bought or sold.