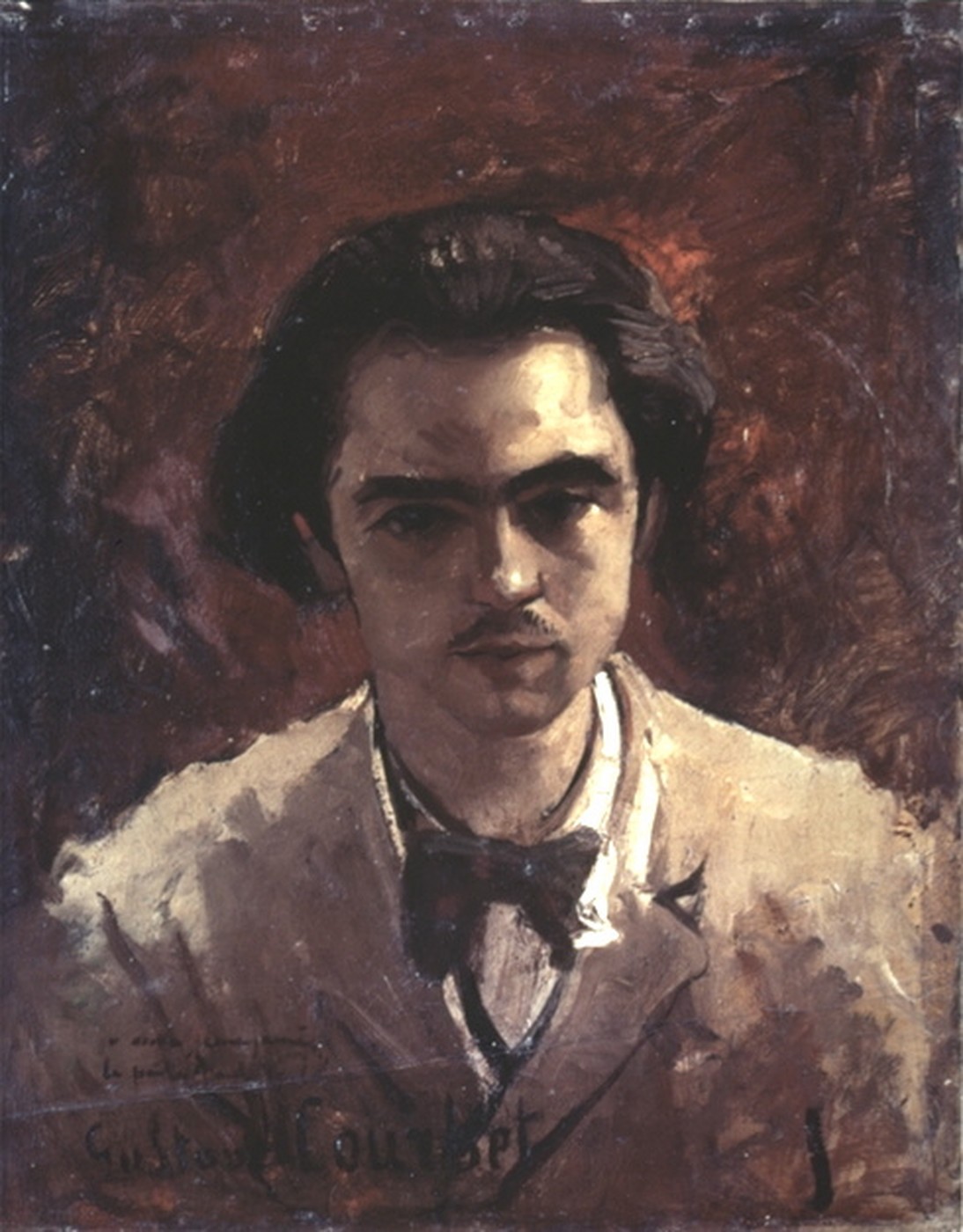

Photo from Macallan Scotch

Here’s a followup on Clayton’s earlier post on Victoria University’s Northrop Frye Gold Medal wines. One of Frye’s diary entries from 1950 recounts drinking at a dinner party with James Thurber that did not go well. On most days through a long working career, however, he liked to drink according to the accepted social standards of the time. Here are some of his observations on and accounts of drinking. (An earlier posting of his Canadian Forum editorial in support of the repeal of Sabbath drinking laws here.)

I knew an old man once who settled for drinking straight Scotch, and he said, “I find it agrees with me.” I find the same thing. (“Chatelaine’s Celebrity I.D.,” Chatelaine 55, no. 11 (November 1982), 43.

Claude Bissell had a few drinks ready for us afterwards before Clawson’s dinner. Very typical of Clawson that his dinner should come on a day when congratulations were being showered on Blissett & me. I drank Scotch very hard & fast & was quite high until I had my dinner. (Diaries, 11 April 1950)

There’s getting to be too damn much God in my life. After lunch I went over to hear Crane’s paper on the history of ideas, but instead of staying for the discussion after tea I went off and had three Martinis—Carpenter doesn’t drink and I decided against giving him the handicap of a slug of Scotch, so it was the first drink I’d had in three days. (Diaries, 23 February 1952)

We had dinner at Jean’s hotel and I went along with the two girls to the theatre: they had tickets to Shaw’s Caesar & Cleopatra but I couldn’t get one, as it was the last performance. I waited until the man said it was a waste of time to wait longer, then went home and had a couple of Scotches & went to bed early. (12 April 1952)

Felt very sleepy after Woodhouse’s whisky & didn’t make much out of Vaughan or Traherne. The kids didn’t cooperate either: the final Huxley lecture was brilliant—Freudian slip again—I meant to write wasn’t brilliant. (Diaries, 15 March 1950)

So I sneaked off to collect Helen from some women’s meeting at Wymilwood, and we went down to the Oxford Press to a cocktail, or rather a whisky, party, given for Geoffrey Cumberlege. I couldn’t get much charge out of Cumberlege, but enjoyed the party. (Diaries, 17 May 1950)

In the evening the Macleans had a supper party for the Cranes, and a very good party it was. (Very good of Ken too, as Crane wrote one of his typically slaughterous reviews of Ken’s book). The Grants, the Loves, the Ropers, and Ronald Williams (I suppose because of the Chicago connection) were there (I suppose Mrs. Williams is pregnant again). Martinis to begin with, and whisky afterward, so what with a very late dinner I got sick again afterward. My own damn fault. I was well into my fifth drink before I realized that I’d had practically no lunch. The party did a men-women split, unusual for the Macleans [MacLeans], and we gossiped about jobs and they about curtains. We were, as I faintly remember, beginning to get slightly maudlin about Eliot and Auden just at the end. Douglas Grant of course talked very well, and remained sober enough to drive us home. I suppose a car, to say nothing of children and sitters and things, does make one very temperate. Crane is a very charming man, but remains a most elusive one. (Diaries, 22 March 1952)

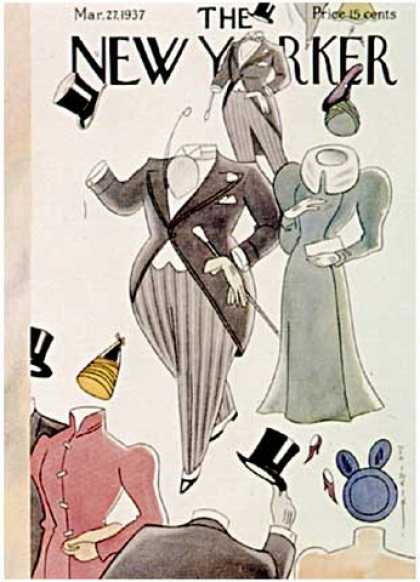

It is not hard to ridicule the fallacy of the distinctive essence, and to show that it is really a matter of looking for some trade mark in the content. A satirical revue in Toronto some years ago known as Spring Thaw depicted a hero going in quest of a Canadian identity and emerging with a mounted policeman and a bottle of rye. If he had been Australian, one realizes, he would have emerged with a kangaroo and a boomerang. One needs to go deeper than ridicule, however, if one is to understand the subtlety of the self-deceptions involved. (“Criticism and Environment”)

I suppose they must have a disease for lies, as they have kleptomania for stealing. This chap had “spent years in the South Seas”: rubber plantations and trading vessels were at the top of the whisky bottle, waving palm-trees and pounding surf around the middle, and island paradises and brown-eyed mistresses near the bottom. It bored me a bit, I must say, and after we’d finished the whisky and he started looking inscrutable over a lighted cigar butt I thought I was in for some pretty involved brooding. (opening paragraph, “Face to Face”) [Frye’s Conrad‑imitation phase]

Marked a few essays & took Helen, who had just finished writing an article for the Star Weekly, out for a cocktail. I had a sidecar, which, I’ve been told, works on the backfire principle: you swallow down one lemonade after another trying to get a faint alcoholic taste in your mouth, when suddenly there’s a dull boom in your stomach, a sudden ringing in the ears, crimson clouds before the eyes, & there you are as drunk as a coot. I had only one, so I don’t know. A businessmen’s dinner was in the dining room, and as I came out I heard the hostess say to the waiter, “How are they getting along with eleven bottles among twelve men?” (Diaries, 5 January 1949)

Ran into Ned [Pratt] & told him my woes. He says Markowitz tells him that evening drinking is the best way to ward off heart disease. He went to the liquor store with me & bought me a bottle of rye. Promised him faithfully I would not have a heart attack in ten years. (Diaries, 11 January 1949)

On the way back [from the library at Harvard] I stopped at a liquor store & asked if there were any formalities about purchasing liquor. He said the formality consisted only in the possession of cash. Even so I didn’t know what to buy, and Canadian rye is $5.75 a bottle—though I think a larger bottle than what we’re allowed to buy. I got a cheaper rye for $3.75, a Corby’s. I must investigate California wines. We came home & had dinner in, after speculating about going out & deciding to renounce the gesture. (Diaries, 14 July 1950––Frye’s 38th birthday)

[Frye tells this story in several places]: In the year of his retirement he [Ned Pratt] turned up unexpectedly at a meeting of the Graduate Department of English (he hated graduate teaching), and sat through three hours and a half of petitions and what not, and then, under “further business,” announced that this was undoubtedly his last meeting of the Graduate Department, and therefore–at which point he produced a bottle of rye. It was a typical gesture, but he was also reminding us of a certain sense of proportion. (“A Poet and a Legend”)