Joseph, in Genesis, has always totally baffled me: he bulks so large and so crucially in the Bible’s greatest book, but what to make of that I don’t see. I’ve encountered several times the assertion that he’s a type of Christ; but what’s really Christlike about him? (Late Notebooks, 337)

What Stevens calls the “metaphor that murders metaphor” [Someone Puts a Pineapple Together, l. 27] is a metaphor not realized to be a metaphor, & so “taken literally.” Note that such an unrealized metaphor becomes metonymic, i.e., the “best available” metaphor, & so starts us on the downward path of authority & hierarchy. The Biblical archetype of this is the dream of Joseph of ascendancy over his brethren, which pushes them all into Egypt. (Late Notebooks, 359−60)

We have recently learned about Frye’s superlatives, but would it not be equally fascinating to have a look at some of his dislikes? Learning that Genesis is the greatest book of the Bible for Frye was not the greatest of surprises, even though I would have voted for Job. However, it has brought to my mind something I have long been intrigued about: why did Frye dislike the story (or rather perhaps the character) of Joseph, “the fruitful bough”? Why did he feel uncomfortable with a story in the greatest book of the Bible, which has been celebrated as one of the best stories ever told?

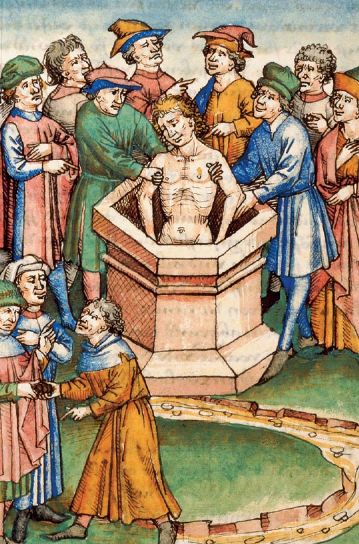

For all I know, Joseph has been recognized by the precritical hermeneutic tradition as one of the fullest types of Christ in the Old Testament. Several church fathers (Ambrose the most eminent among them), whose imaginative readings of the Bible have certainly inspired Frye, note parallels in the story of Joseph and Jesus. Both are despised and rejected by their brethren. Both are sold by pieces of silver and descend into the pit which symbolizes darkness and death. Joseph, as well as Jesus, is tempted and goes through trials before his ascension, as it were, to glory. Prefiguring the Eucharist, Joseph ultimately becomes the saviour of the people by nourishing them from the Egyptian granaries, etc. A perfectly U-shaped narrative, mirrored in countless literary tales, apparently a brilliant example for the order of words. Then why the dislike?

Of course we can find hints in Frye’s work pointing towards a possible explanation. Apparently, despite its literary perfection and archetypal depth, he couldn’t help seeing Joseph’s story mostly as a myth of authority, manifested in immature adolescent dreaming for ascendancy over siblings, ultimately an unconscious craving for power and glory. For a thinker with such a high evaluation of dreams and desires, calling certain dreams “agressive and self-promoting” (Words with Power 235) is very strong language. What turns dreams into an ideology of power, Frye interestingly suggest, is interpreting them literally, just like Joseph did in the first phase of the story. (Later, however, Joseph does become a very creative interpreter of dreams, which, although mentioned in Words with Power, is not really considered a character development.) Frye, who attributed great importance to Jesus’ rejection of wordly power beginning with the temptation scene (see RW 210) and ending with the cross, certainly did not consider Joseph “Christ-like” in his craving for and exercise of power.

This takes me to perhaps the profoundest reason for Frye’s dislike. To interpret Joseph as a type of Christ is not the only possible symbolical reading of this narrative. In the Egyptian scenes, Joseph quite relentlessly manipulates his brothers with a noble purpose in view: to make them confront their past crime and elicit a change of heart in them. In short: here is the trickster God of the Old Testament toying with human beings, a father figure who disciplines those subjected to him from a position of authority, a vision of God Frye felt uncomfortable with. If we argued that Joseph’s rule here prefigures the exaltation of Christ, his resurrection and ascension, Frye would probably answer that the proper type of Christ’s resurrection in the Old Testament is the Exodus, a deliverance from Egypt and not an arrival into it.

Actually, it was Luther, himself suffering at the hands of an incomprehensible and hidden God, who provided the classic interpretation of Joseph’s doings as an allegory of how God works in the world. Luther conceives of this world as a delusive play of appearances, where God, as it were, has to hide himself and perform tricks or inflict sufferings in order to achieve his good and merciful purposes. Repulsive as this vision may seem to a follower of Blake, a note by the late Frye I have already quoted elsewhere resonates surprisingly with Luther’s ideas: “God’s power works only with wisdom & love, not with folly & hatred. As 99.9% of human life is folly & hatred, we don’t see much of God’s power. He must work deviously, a creative trickster, what Buddhists call the working of skilful means.” (Late Notebooks 212) If Frye had approached the story in Genesis with a focus on the “folly and hatred” of Joseph’s brothers, he might have seen less a power display in Joseph’s attitude and perhaps more a tact and wisdom which not only inflicted pain on others but also on himself. It is not a negligable detail that Joseph wept three times with increasing intensity behind his mask.