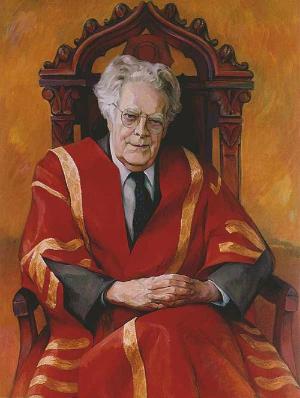

Here is Clayton Chrusch’s summary of the second chapter of Fearful Symmetry. (His summary of chapter one can be found here):

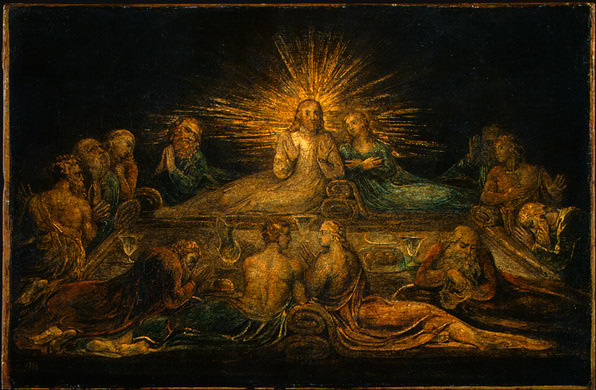

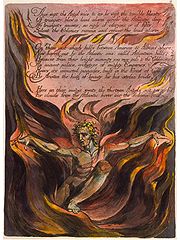

Fearful Symmetry Chapter Two: The Rising God

Man is All Imagination. God is Man & exists in us & we in him.

1. God is the fully developed human imagination.

This chapter presents Blake’s theology. His theology is based on the identity of God with humanity and in particular with the fully developed human imagination. God must be human because we cannot perceive anything greater than human. Since existence is perception, nothing superhuman can exist. Furthermore, the fact that Jesus was fully God and fully man means that God posseses no attributes which are not human.

We are God in our perceptions. No one can perceive God, but when we perceive the particular, we perceive as God. An egotistical perception sees a general reality, but a divine perception sees a particular reality. Blake calls the perception of a general reality experience, and the perception of a particular reality innocence.

What is true of perception is true of creation–when we create, we create as God. Frye writes, “all creators are contained in the Creator.” For Blake, worshipping God means honouring the creativity of human beings, and honouring most those with the most developed imaginations. The more people suppress their imaginations, the more they turn their backs on God, that is, their own divinity. But turning our backs on our divinity also means turning our backs on our humanity–it is what is great in us that makes us human, not what is small. God is the species, and humans are individuals of that species. God is the essence, and we are the identities arising from that essence. God is the body, and we are the limbs.

2. Against God as a designer

It’s wrong to look to Blake for an informed opinion of all things. There are some things that Blake was simply not interested in. He was not interested in mathematics, for instance, and though he may seem to disparage it, a sympathetic reader will realize that Blake is really attacking superstitious uses of mathematics. These include occult math, that is, numerology, and the kind of scientific reductionism that sees reality as merely an abstract mathematical design rather than the concrete mental creation that it is.

In some of Blake’s poems, Blake uses numbers and diagrams, but these are part of the imaginative unity of the poems and do not indicate “any affinity with mathematical mysticism.”

Blake could not bring himself to believe in a God that is a designer rather than a creator.

3. Against God as an impersonal and mechanical power

Blake dislikes Newton partly because of the kind of theology that Newton’s universe suggests. Such a vast universe governed by mechanical laws suggests a God that is a great impersonal and mechanical power. Such a theology would be further encouraged by the 19th century discovery of “the immense stretch of geological time, in which nothing particularly cheerful seems to have occurred.” Such a God is distasteful to Blake not only because it must be a tyrant, but because it reduces the whole universe and all of life to less than conscious activity.

Blake agrees with the followers of the Newtonian Gods that God is the essence of life. But the followers of Newtonian Gods discover the essence of life by abstracting life until they get to the simple idea of motion. This is the same lowest-common-denominator approach to discovering reality that Blake hates so much in Locke. Blake sees that, of all beings, humans are most alive and so the essence of life is found in human attributes such as intelligence, imagination, judgment, and conscious purpose. And so God must possess all these attributes.

As for evolution, a Blakean must interpret it not as a mechanical process of stimulus and response, and certainly not as intelligent design, but as an exuberant imaginative development in all possible directions.

Blake did not idealize nature and possessed no illusions about “noble savages” living in a state of nature. Nature is cruel, and anything living in a state of nature is savage. Nature achieves its highest form where both it and people are cultivated. For Blake, the central symbol of the imagination is a city, in other words, a world and a nature with a human form where the imagination “has developed and conquered rather than survived and ‘fitted.'”

Continue reading →