“Casey Jones” in the blog ceci n’est pas un journal has a post referencing Fearful Symmetry and Menippean satire here. He also produces this pungent little quote from the New York Review of Books: “It seems to me that Derrida in context is even worse than Derrida out of context” (hit the link and scroll all the way down to the end, just before the Notes).

Monthly Archives: April 2010

Bob Denham: “Pity the Northrop Frye Scholar”? Anatomy of Criticism Fifty Years After

Bob Denham’s talk to the Frye Festival in April 2007 has been added to the Festival Archive in the journal. It can be linked directly here.

A sample:

In his foreword to the reissue of the Anatomy in 2000 Harold Bloom remarks that he is “not so fond of the Anatomy now” as he was when he reviewed it forty‑three years earlier (vii). Bloom’s ambivalence springs from his conviction that there is no place in Frye’s myth of concern for a theory of the anxiety of influence, Frye’s view of influence being a matter of “temperament and circumstances” (vii) Bloom’s foreword, however, is devoted chiefly, not to the Anatomy, but to his own anxieties about Frye’s influence, presented in the context of his well-known disquiet about what he calls the School of Resentment––the various forms of “cultural criticism” that take their cues from identity politics. In the 1950s, Bloom says, Frye provided an alternative to the New Criticism, especially Eliot’s High Church variety, but today he is powerless to free us from the critical wilderness. Because Frye saw literature as a “benignly cooperative enterprise,” he is of little help with its agonistic traditions. His schematisms will fall away: what will remain is the rhapsodic quality of his criticism. In the extraordinary proliferation of texts today, according to Bloom, Frye will provide “little comfort and assistance”: if he is to afford any sustenance, it will be outside the universities. Still, Bloom believes that Frye’s criticism will survive not because of the system outlined in the Anatomy, but “because it is serious, spiritual, and comprehensive” (xi).

Frye on Haydn

Further to Michael’s post, Frye on Haydn in Notebook 5

If I had such a thing as a favorite composer, it would be Haydn. I think it’s Haydn anyway. I’m going to write something on him someday. More and more I find myself turning to Bach & Haydn, which means more & more away from Mozart. Mozart’s a skeptic & Haydn’s a Christian. Haydn has everything. He has all of Schubert’s ease of melody sags or goes soupy the way Schubert does. He’s as witty as either Mozart or Scarlatti: I’ve just read through 37 minuets & 24 German dances, a grueling test for any composer & he says something pointed & epigrammatic practically every time. But he has more than wit: he has an amazing eloquence & range in his melodic line: he can be marvellously “singable” & yet swoop over everything form a soprano to a bass range: D major sonata in Book I with the lovely long Adagio. He may not be as profound a thinker generally as Mozart, but I think he’s a greater thinker in musical form than Mozart: he has a sense of organic unity about him & an originality of creative thought, still in musical form, Mozart hasn’t. Haydn develops a plot; Mozart works out a situation. But the plot really develops, that’s the point. He had much more influence over Beethoven than Mozart, I think, particularly in things like the Pathétique: only Beethoven is analytic & disruptive where Haydn is synthetic. He’s really almost more radiant than Beethoven for that reason. His trios are more fun to read on a piano than Mozart’s because they’re all piano & Mozart’s are balanced: Mozart’s are more expertly written, but it’s plot & situation again, & Haydn’s more fun. In things like the G major sonata, Book II, slow movement, his impersonality, gone serious, just drops you out of sight: he’s too wrapped up in pure music ever to be sad or cynical, like Mozart. He hits cold depths of ice Mozart doesn’t get down to because he doesn’t believe enough. Sometimes the coldness of pure Rococo, the winter-chill of our autumnal culture: slow movement of C major quartet, op. 59 No. 2 or something in the fifties: 55, I guess. But that doesn’t mean he’s an abstract music writer. Sometimes Bach is unplayable, either because, as in the Art of Fugue, he’s just writing absolute music, or because he’s gone beyond all reading or reproduction into pure thought, as in the C# minor of the WTC I [The Well-Tempered Clavier, book 1]. Sometimes Beethoven’s unplayable when he’s appealing to a wrench in the guts too physical for a performance to reach, as in the Coriolan or the 106. (That doesn’t necessarily mean greatness, any more than an unactable play is necessarily great because King Lear is unactable). But Haydn always has a powerful ease of reproduction: his music exists only for performance. His piano sonatas are in one idiom, his string quartets in another, etc. That’s why he’s the easiest of all composers to play: he thinks so purely in terms of the genius of reproducing instruments. Hence he’s an amateur-family musician, and could do what the Bible could almost have done (not quite: its achievement is overrated) for amateur-family English prose style. He’s probably the only great composer who could have written a national anthem. But he’s got something ultimate in his time & Mozart & Beethoven & Goethe haven’t: there’s too much Goethe in Mozart and too much Beethoven in Goethe. Something of the rebirth of imagination: the thing Blake had. Haydn was no Bach and couldn’t do the Mass or Passion job to save his soul, if it had ever been in any danger, but the Creation does give the perfect Paradise-existence of the imaginative mind: the super-pastoral note. I daresay the Seasons is the same thing: I haven’t heard or read it, but winter is as pastoral an idea as summer. He’s been so grossly underrated for the same reason that Mozart used to be: a supreme genius of comedy, patted on the back for being amusing, like Dan Chaucer and gentle Shakespeare—the Papa Haydn approach. Chaucer, being ironical, is Mozartian; Haydn’s closer to the 13th c. (Notebook 5, CW 25, 163–5)

Frye and Helen Kemp on A. Y. Jackson

Further to Michael’s post, Frye and Helen on Jackson in the Correspondence.

Canadian landscape painting has to deal with a sharp hard light and solid blocks of clear colour: consequently a tendency to conventionalize outlines has been inherent in it from the first. Thomson, being interested in problems of linear distance and in the breaking up of light which they suggest, dodged this tendency, but it is strong in Jackson and Emily Carr, and of course far stronger in Lawren Harris, who saved himself from dropping into a facile formula (like Rockwell Kent) by turning to out-and-out abstract painting. (CW 12, 12)

The Group of Seven felt that they were among the first to look at Canada directly, and much of their painting was based on the principle of confronting the eye with the landscape. This made a good deal of their work approach the flat and posterish, but that was a risk they were ready to take. Jackson, Lismer, and Harris all found this formula exhaustible, and have all developed away from it. Thomson and Emily Carr represent a more conscious penetration of the landscape: they seem to try to find a centre of rhythm deep within their subject and expand from there. Milne combines these techniques in a way that is apt to confuse people who look at him for the first time. (CW 12, 73)

I am, of course, deeply appreciative of the honour that Carleton University has done me. It is particularly an honour to receive this degree in the company of Mr. A.Y. Jackson, as well as a great pleasure, because Mr. Jackson is an old friend. (CW 12, 272)

Writers don’t interpret national characters; they create them. But what they create is a series of individual things, characters in novels, images in poems, landscapes in pictures. Types and distinctive qualities are second-hand conventions. If you see what you think is a typical Englishman, it’s a hundred to one that you’ve got your notion of a typical Englishman from your second-hand reading. It is only in satire that types are properly used: a typical Englishman can exist only in such figures as Low’s Colonel Blimp. If you look at Mr. Jackson’s paintings, you will see a most impressive pictorial survey of Canada: pictures of Georgian Bay and Lake Superior, pictures of the Quebec Laurentians, pictures of Great Bear Lake and the Mackenzie River. What you will not see is a typically Canadian landscape: no such place exists. In fiction too, there is nothing typically Canadian, and Canada would not be a very interesting place to live in if there were. Only the outsider to a country finds characters or patterns of behaviour that are seriously typical. Maria Chapdelaine has something of this typifying quality, but then Maria Chapdelaine is a tourist’s novel. (CW 12, 275)

A. Y. Jackson

Wilderness, Deese Bay

On this date in 1974 A. Y. Jackson died.

Frye in “Culture and the National Will” (regarding the way in which artists — literary ones included — create the national landscape):

If you look at Mr. Jackson’s paintings, you will see a most impressive pictorial survey of Canada: pictures of Georgian Bay and Lake Superior, pictures of the Quebec Laurentians, pictures of Great Bear Lake and the Mackenzie River. What you will not see is a typically Canadian landscape: no such place exists. (CW, 12, 275)

Vintage CBC report on the Group of Seven and the Rheostatics after the jump.

Update from the Frye Festival

The child sex abuse scandal that’s rocking the Roman Catholic Church guarantees that Linden MacIntrye’s The Bishop’s Man will continue to chart the bestseller list for a while longer. Winner of the Giller Prize last fall, it’s well worth the read, topical or not. In an interview last fall, in connection with his winning the Giller, MacIntyre talked about what draws him to the novel. As a journalist with CBC’s ‘The Fifth Estate’ he has covered the story of the church’s attempts to cover up incidents of sexual abuse. The novel allows him to do something that he cannot do as a journalist. It allows him to go inside the minds of his characters. It allows him to inhabit his characters and bring them to life as full human beings, with all their virtues and vices.

In his book This Is My Country, What’s Yours? A Literary Atlas of Canada, Noah Richler takes up this same question as to what makes the novel special and seemingly immune to constant threats to kill it off. “What sets the novel apart is the ‘imaginative leap’ that its author makes in order to create and then inhabit a character, and that its readers make in turn. This simple dynamic is what gives the novel its identity. … And in this assumption that readers make – that we are all, at some base level, alike – lies the magnanimity, but also the aggressive and even colonizing impulse of the novel. For the novel is a hegemonic thing, righteous on behalf of a certain conception of humankind’s place in the world.”

The novel does what other forms of storytelling (such as the epic and the mythic stories that we associate with “oral” societies’) cannot do. Again quoting Richler: “The novel says, ‘For me to know you and portray you in good faith, I must remember that you and I are fundamentally alike. Perhaps only circumstance is what has made us different’.” Novelists do their work by “putting themselves in their protagonists’ shoes and making that imaginative leap, no matter their creations’ extremities of character.” There is no absolute evil in the novel, as there is in the epic and in creation myths. The worst characters in a novel are still human beings, like all the rest of us. “This quality puts the novel close to be an ‘end of narrative,’ if you like – a form of story that is as versatile and enduring as the belief in human rights that it reflects.”

Others have less faith, or no faith at all, in the novel’s versatility and endurance. Books heralding the death of the novel are nothing new, and the latest is David Shields’ Reality Hunger. The novel as we know it, with its linear plot and defined character, is, Shields believes, dead – or worse, irrelevant. “Conventional fiction teaches the reader that life is a coherent, fathomable whole that concludes in a neatly wrapped-up revelation. Life, though – standing on a street corner, channel surfing, trying to navigate the Web – flies at us in bright splinters.” Our reality is fragmented, chaotic, asymmetrical, elusive and noisy, and since reality is what we hunger for, the conventional novel is obviously inadequate for the task. It’s a throwback to a bygone era. We need something new. Shields’ prescription is what he calls the ‘lyric essay’ – based on the collage technique, the structural equivalent of our splintered reality.

Easter

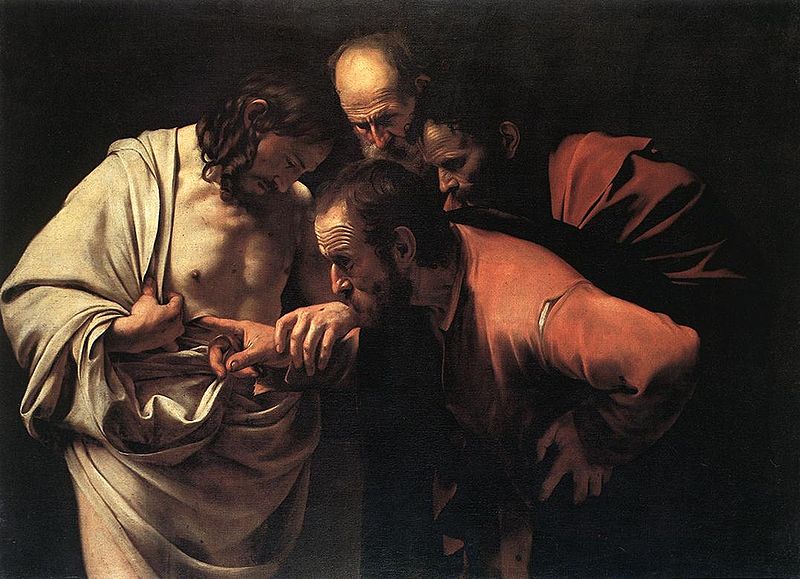

Caravaggio’s The Incredulity of Saint Thomas, 1601

From the Late Notebooks:

When Jesus says “I am the way” [John 14:6] time stops. There is no journey through unknown country: all the disciples have to do is walk through the open door (another “I am” metaphor [John 10:9]) of the body in front of them). That is, I think, impossible before the Resurrection. Perhaps everything that happens in the gospels is not an event but a ticket to a post-Resurrection performance. Except that the spiritual reality is not so much future as an expansion of the imaginative possibilities of the present. The myth confronts: it doesn’t prophesy in the sense of foretelling. (CW, 5, 159)

Jesus is not “a” historical figure: he’s dropped into history as an egg is into boiling water, as I said [par. 301], and essentially “the” historical Jesus is the crucified Jesus. One can understand why the Gnostics tried to insist that the crucifixion was an illusion, but nobody can buy that now. The pre-Easter Jesus answers the question: ‘Can a revolt against Roman power succeed?”

The answer is no, and the pre-Easter Jesus sums up the history of Israel, which is a history of “historical” failure. (CW, 5, 170)

The Resurrection, then, is the marriage of a soul & body which forms the spiritual body. The body part of this marriage is female: the empty tomb is recognized solely by women, except perhaps for that fool who stuck Peter into John’s account [20:1-10]. (Perhaps the “and Peter” of Mark [16:7] was stuck in too.) The fact that Jesus took on flesh in the Virgin’s womb has certainly been dinned into Christian ears often enough; but the fact that he took on flesh in the womb of the tomb at the Resurrection, and that there’s a female principle incorporated in the spiritual body, seems to have been strangled. The real tomb of Christ was the male-guarded church. (CW, 5, 327)

The historical Jesus is a concealed though essential element in the Gospels: if the Gospels’ writers had simply made up the Jesus story they would still be superb works of literature, but of course they wouldn’t be gospels. The myth is what they literally are, though: they don’t present Jesus historically. Historically, Jesus is a man until the Resurrection, when he becomes an element in everyone, implying that no one can be “saved” (meaning the indefinite persistence of something like an ego in something like a time and space) outside or before Jesus. Presented as a myth in the eternal present, this doctrine takes on a more charitable appearance. The Word and Spirit in man then coincide into something that has its being in God (as God has his being in it) to such an extent that the question of belief in “a” God doesn’t arise. (CW, 6, 671)

From CBC radio “Rewind”, various Easter broadcasts dating back to the 1940s, including Frye in 1973 on Easter myths and symbols (beginning at the 24 minute mark).