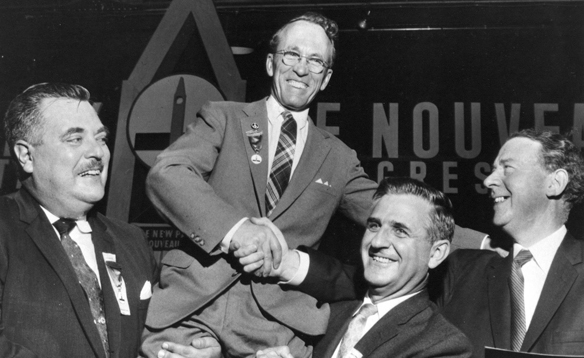

Tommy Douglas (former CCF Premier of Saskatchewan and father of Medicare) becomes the NDP’s first leader, holding the post until 1971

On this date in 1961 the New Democratic Party was formed with the merger of the Cooperative Commonwealth Federation and the Canadian Labour Congress.

Frye on Canadian Socialism in his “Speech at the New Canadian Embassy, Washington,” September 14, 1989:

….Canada has had, for the last fifty years, a Socialist (or more accurately Social Democratic) party which is normally supported by twenty-five to thirty percent of the electorate, and has been widely respected through most of its history, for its devotion to principle. Nothing of proportional size or influence has emerged among socialists in the United States. When the CCF, the first form of this party, was founded in the 1930s, its most obvious feature went largely unnoticed. That feature was that it was following a British rather than an American tendency, trying to assimilate the Canadian political structure to the British Conservative-Labour pattern. The present New Democratic Party, however, never seems to get beyond a certain percentage of support, not enough to come to federal power. Principles make voters nervous, and yet any departure from them towards expediency makes them suspicious. (CW 12, 643-4)

CBC Radio archives on Tommy Douglas and the NDP here.

CBC Television memorial for Tommy Douglas here.