httpv://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RVJyaJ5TNpc

PBS documentary on Einstein

On this date in 1905 Albert Einstein published “On the Electrodynamics of Moving Bodies” laying out his special theory of relativity.

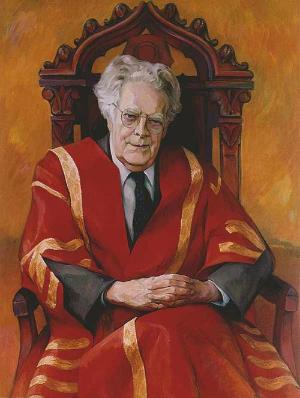

Frye on Einstein in a 1981 interview with Acta Victoriana:

Interviewer: In 1938 Einstein said that “Physical concepts are free creations of the human mind, and are not, however it may seem, uniquely determined by the external world.” Did Einstein’s recognition of the fictional, or, if you like, mythical status of physical concepts open up a new common ground between the activity of the scientist and the activity of the poet?

Frye: Oh, I think so, yes, and I think Einstein knew that. He was really saying that science is mental fiction just as the arts are and that the question of what is really there underneath the construct we put on it is only a kind of working consensus. If a painter looks at railway tracks stretching out to the horizon he will see them meeting at the horizon. But, as Margaret Avison says, “a train doesn’t run pigeon-toed.” You would get on the train if you knew that was really true; so that what is really there is a matter of working consensus. Similarly, you can prove mathematically the atomic construction of protons and neutrons and electrons inside an object like this desk, but as a matter of ordinary social working consensus you keep on bumping into it. . .

Interviewer: In the Anatomy of Criticism you suggest that “criticism” must be understood as an organized body of knowledge about art in the same way that “physics” is understood as an organized body of knowledge about nature. If this understanding of criticism is generally accepted in the intellectual community, will humanists and scientists find themselves in a more fruitful dialogue?

Frye: Yes, I think they would. With the big revolution in physics that began with Einstein and Planck, you have the principle established that it’s no longer sufficient to work in a world where the scientist is the subject and the world that he’s watching is the object, because the scientist is an object too; the act of observation alters what you are observing. That of course does bring the arts and sciences close together in a common meeting ground. The social sciences, which are very largely twentieth-century in origin, are entirely founded on the need to observe the observer. I think of criticism as ultimately a form of social science. Of course, that cuts across a lot of conditioned reflexes, and I first said that in the days when my humanist colleagues thought that what characterized the social scientist was that he wrote very badly. Well, an awful lot of literary critics write very badly too, so that’s not a very safe dividing point. I think that criticism can never be a science in the physical scientist’s orbit, that is, it can never be quantified experimentally and lead to prediction. It’s something else; it’s more like a kind of cultural anthropology or certain forms of psychology. (“Scientist and Artist,” CW 24, 531-2)

Frye interviewed by Loretta Innocenti in 1987:

A work of literature is the focus of a community. Different people will read it differently, agree and disagree about it, and eventually some kind of consensus emerges. This consensus is the objective residue, what remains after the subjectivity of individual approaches becomes increasingly dated. Much the same thing happens in the sciences — for example, Einstein made invaluable contributions to the contemporary picture of the physical world although he never really accepted the quantum randomness of that picture. (“Frye, Literary Critic,” CW 24, 827)

Frye interviewed by Harry Rasky in 1988:

Rasky: Is there any easy way of defining God?

Frye: You can’t define him at all. It’s not a definable word.

Rasky: I remember asking Chagall that question and he shrugged his shoulders and said, “Well, even Einstein couldn’t define that.”

Frye: Einstein wouldn’t try. (The Great Teacher, CW 24, 869)

Continue reading →